- Search

| Ann Rehabil Med > Volume 41(3); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

To develop and test the validity and reliability of a new instrument for measuring the thigh-foot angle (TFA) for the patients with in-toeing and out-toeing gait.

Methods

The new instrument (Thigh-Foot Supporter [TFS]) was developed by measuring the TFA during regular examination of the tibial torsional status. The study included 40 children who presented with in-toeing and out-toeing gaits. We took a picture of each case to measure photographic-TFA (P-TFA) in the proper position and to establish a criterion. Study participants were examined by three independent physicians (A, B, and C) who had one, three and ten years of experience in the field, respectively. Each examiner conducted a separate classical physical examination (CPE) of every participant using a gait goniometer followed by a TFA assessment of each pediatric patient with or without the TFS. Thirty minutes later, repeated in the same way was measured.

Results

Less experienced examiner A showed significant differences between the TFA values depending on whether TFS used (left p=0.003 and right p=0.008). However, experienced examiners B and C did not show significant differences. Using TFS, less experienced examiner A showed a high validity and all examiner's inter-test and the inter-personal reliabilities increased.

Children presenting with an in-toeing or out-toeing gait are one of the most common pediatric foot problem seen by physiatrists. Although a lot of research for in-toeing and out-toeing gait, etiologies of these conditions are still debated. But there are many opinions that the structural conditions giving rise to in-toeing or out-toeing can be correlated with the age of onset.

Tibial torsion has also been known as one of the important structural problems in in-toeing or out-toeing gait [1,2,3,4]. The most common measurement methods of the tibial torsion are the classical physical examinations (CPE) and computed tomography (CT) scan. In many studies, CT scan has been proven to the point of validity and reliability for the causal analysis of tibial torsion [5,6,7]. However, to conduct a CT scan is difficult to use, expensive and rarely available in the clinical setting for every child with in-toeing and out-toeing gait or to monitor each stage of progress. For routine clinical evaluation, CPE remains the primary method for assessment. To be useful, this examination should give acceptably reproducible results that can be compared with an established range of normal values [8].

Thus, this study attempted to develop a new instrument for the CPE of the thigh-foot angle (TFA) measurement which is one of the most popular examinations of tibial rotational problems. Moreover, this study intended to evaluate the validity and reliability of the new instrument.

The present study was a prospective observational, cross-sectional study and the subjects were 40 children under the age of 15 who visited the rehabilitation outpatient clinic for in-toeing or out-toeing gait. They consist of 13 men and 27 women of average age 81.58 months (SD=24.21). Patients with central nervous system diseases such as cerebral palsy, musculoskeletal diseases such as joint dysplasia of leg, contracture of joints and muscles, and various foot deformities are excluded.

The Institutional Review Board of Presbyterian Medical Center approved the protocol, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

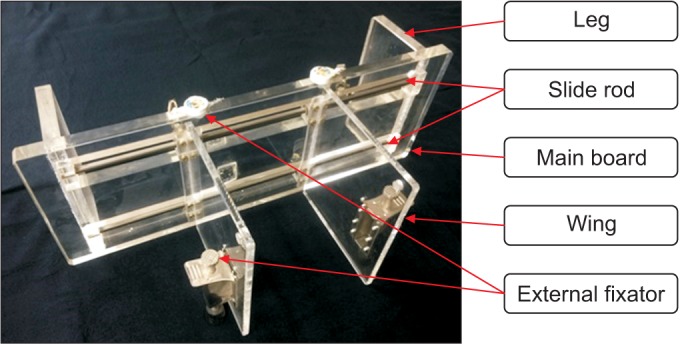

The newly designed and developed ‘Thigh-Foot Supporter (TFS)’ is made of acrylic and consists of the main board and two wings. The wing is movable from side to side by two slide rods located above and below the main board under the control of patients then the rotation of thigh is prevented by fixation. Two external fixators were produced using the absorption force and bottom fixation force for fixation of both wings, respectively. In the prone position, weights of lower extremities could be supported by legs with 90° of knee flexion (Fig. 1).

Dermographic investigation and history of the children who were complaining the in-toeing or out-toeing gait were taken then physical examinations were performed. Patients' history consist of birth history, family history and the past and present medical history. Measurement of range of motion was done at the hip, knee and ankle joints. Children are deemed reasonable basis except through the history taking, and physical examination was excluded from the study. According to Rethlefsen et al. [9], incoming gait can be defined to show over 0° of the foot progression angle to point inward in more than 50% of the walking cycle. So, children were asked to walk straight towards the examiners on a straight line to measure the foot progression angle and divided into an in-toeing and out-toeing gait group. Also, we have checked the generation side, bilaterally or unilaterally.

When the walking pattern is confirmed, the photo shoot was taken for defining a reference value for measurement validity via photographic-thigh-foot angle (P-TFA). To measure the P-TFA, we let the children lie in the prone position and keep knee joints at 90° of flexion, ankle joints in neutral, the sole in the parallel to the floor; then we took photos to show both thighs and feet.

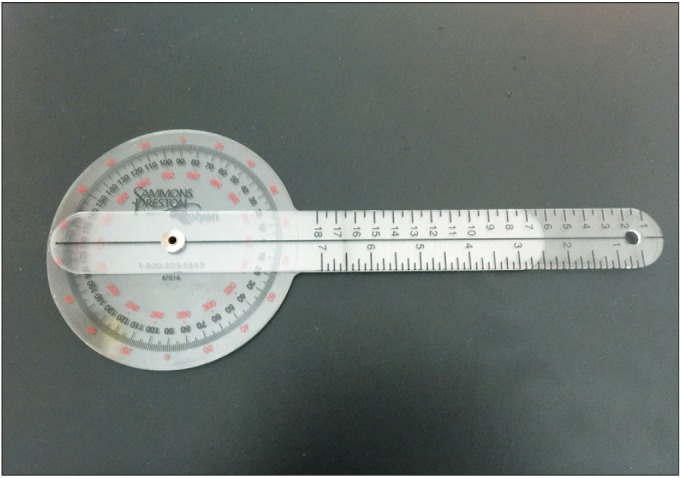

Three examiners with different experiences of the TFA measurement—examiner A with at least 1-year experience of the TFA measurement, examiner B with 3-year experience of TFA measurement, and examiner C with 10-year experience of the TFA measurement—measured the TFA using a goniometer. All examinations were performed using a standard universal goniometer, which uses 1 increments with an arm length of 18 cm (Fig. 2) randomly in separate rooms. An initial assessment with a gait goniometer was performed during the first CPE. Thereafter, the TFE was measured twice with a goniometer and the TFS. The angle formed by each line that divides the longitudinal axis of the thigh and calcaneus was measured in a prone position with the knees bent at an angle of 90° and the ankle kept in the neutral position. The negative value refers to the internal rotation of the tibia whereas the positive value refers to the external rotation [10]. Approximately 30 minutes after obtaining a scan of the foot, the TFA was measured again in the same way. Examiners were blinded as to the measurements obtained by their co-investigators (Figs. 3, 4).

A paired t-test study was conducted to compare and analyze the changes of the measurement values and differences of TFA compare to the P-TFA before and after using the TFS. Repeated measure ANOVA was conducted to analyze the inter-personal changes before and after using the TFS. Also, the inter-test and inter-personal consistencies were analyzed using the intra-class correlation (ICC). Because repeated measure ANOVA test failed to satisfy the sphericity test, Wilks' lambda was used; inter-personal differences were post-analyzed using the Bonferroni main effect tests. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS ver. 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and analyzed at the significance level of 5%.

A total of 34 out of 40 children (85%) showed in-toeing gaits, while 6 children (15%) showed out-toeing gaits. Intoeing and out-toeing gaits were observed on both sides of 38 children and on only one side in 2 children (Table 1).

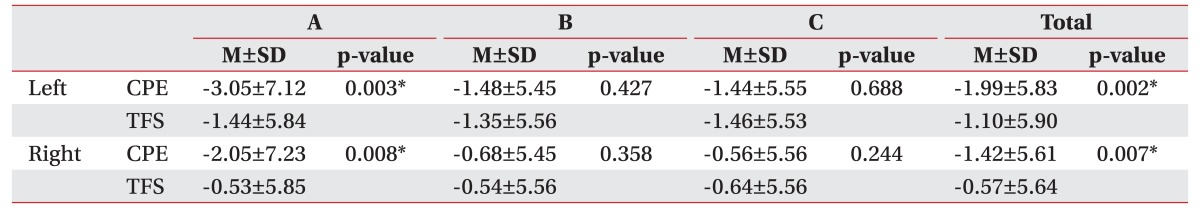

The differences of the TFA measured without and with TFS, respectively were analyzed. Examiner A obtained average values measured at the left leg which was -3.05° without using TFS and -1.44° when using TFS, and the measurement at the right leg was -2.05° without TFS and -0.53° with TFS. Although the examiner A showed significant differences in both leg (left p=0.003 and right p=0.008) depending on using TFS, but the examiners B and C didn't show significant differences depending on using TFS (Table 2).

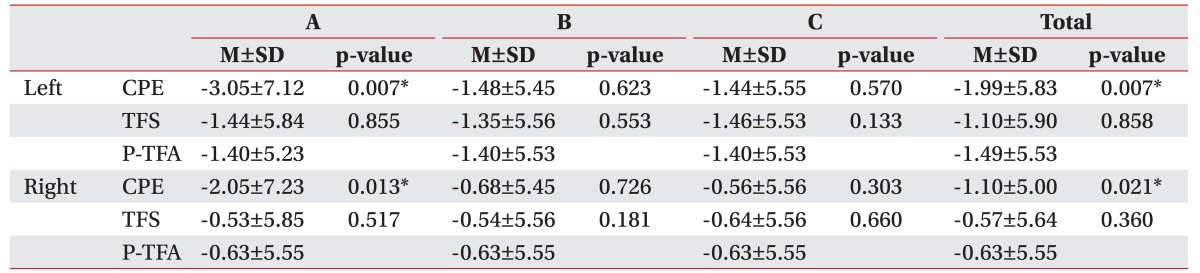

When the TFA values measured by the CPE were compared to the P-TFA, although the examiner A showed significant differences in both legs (left p=0.007 and right p=0.013), examiners B and C did not show significant differences. But the three examiners A, B, and C didn't show significant differences in TFA values using TFS compared to the P-TFA (Table 3).

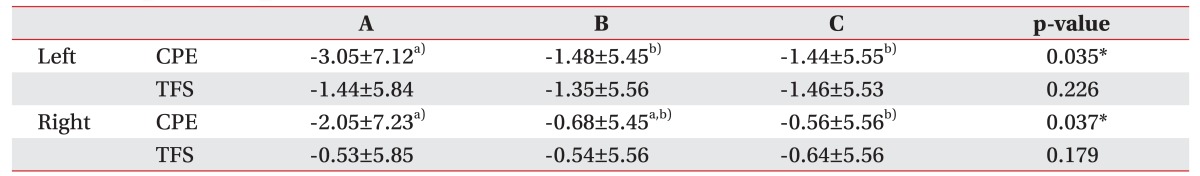

To show the inter-personal differences before and after using TFS, we performed an analysis using the repeated measure ANOVA. Significant inter-personal differences among three examiners were shown when measuring TFA with the CPE but were not shown when measuring with TFS. In particular, the examiner A showed more significant differences before and after TFS compared to the examiners B and C (Table 4).

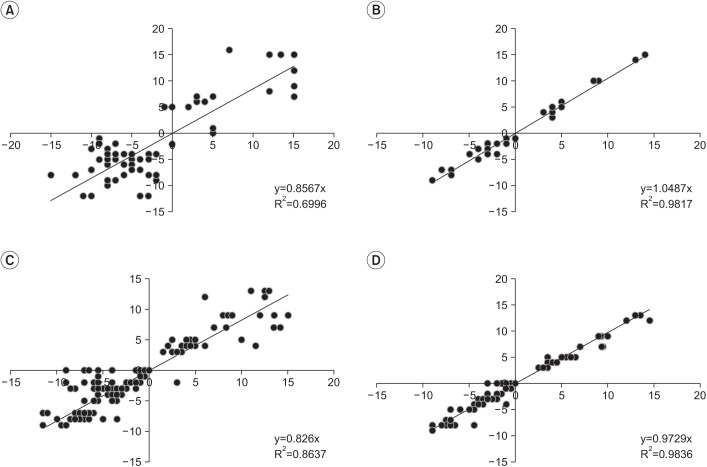

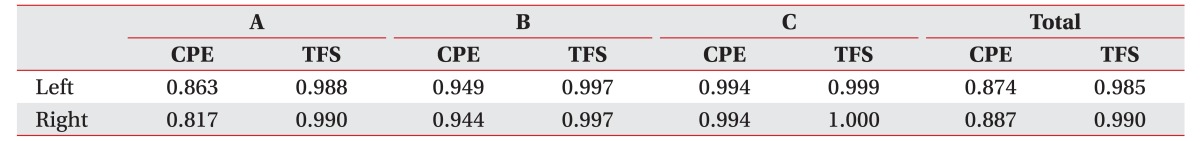

The inter-test and inter-personal consistencies were analyzed with ICC test to evaluate the reliability of the results of TFA measurement by examiners A, B, and C. Examiners A showed different consistencies of 0.863 and 0.817 at the left and right leg, respectively, when measuring the TFA with the CPE, and 0.988 and 0.990 with TFS showing the increased consistencies. Examiner B showed increased consistencies in which 0.949 to 0.997 on the left leg and 0.944 to 0.997 in the right leg with both the CPE and TFS; examiner C also showed increased consistencies in which 0.944 to 0.999 on the left leg and 0.944 to 1.000 at the right leg. The results of analyzing the interpersonal consistencies also showed increased consistencies in both legs with TFS in which 0.874 to 0.985 at the left leg and 0.887 to 0.990 at the right leg (Table 5, Fig. 5).

The main aims of this study were to evaluate whether the newly developed TFS could be used for valid and reliable measurements, i.e., if a constant value could be obtained from repeated measurements. Since measurement error is decreased when the validity and reliability of instruments are improved, consistent results are possible when conducting serial measurements in outpatient clinics. It will also be an enormous help in providing counsel to parents of children with orthopedic issues or to plan further treatment.

Common lower extremity abnormalities in children can be attributed to two types of rotational problems, i.e., pronation and supination. There are three types of deformity it has metatarsus adducts or abductions, internal or external tibial torsion, and increased femoral anteversion or retroversion. An accurate diagnosis can be made by carefully documenting the medical history of each pediatric patient and by performing a CPE in order to ascertain the torsional profile of the lower extremities. Charts of normal values and values with two standard deviations for each component of the torsional profile are available. In most cases, the abnormality improved with time. A careful physical examination, explanation of the natural history, and serial measurements are important in order to develop an individualized treatment plan [3].

In-toeing and out-toeing gaits can appear in one or more parts of the lower extremities, including from the hip joint to the femur, knee joint, tibia, ankle joint and foot [1,11,12]. Most in-toeing and out-toeing gaits do not require correction; however, an altered gait beyond the normal range, i.e., above two standard deviations of the torsional profile may result in long-term disability or restricted movement, e.g., arthritis, restriction of normal functions such as pain after exercise and a tendency for frequent falls. Therefore, it is important to accurately diagnose the causes of in-toeing and out-toeing gaits in children and to develop a treatment plan that takes into account changes that may occur as they grow up to become adults [1,10].

The tibial torsion has been known as a major factor among many other causes for the development of intoeing and out-toeing gaits [1,2,3,4]. It affects males and females equally and is often asymmetrical with the left side affected more than the right side. The exact cause is unknown but is believed to be the intrauterine position, sleeping in the prone position after birth, and sitting on the feet. Internal tibial torsion gradually improves on its own by the time the child reaches 8 years of age in 90% of the cases [13].

Internal or medial tibial torsion can manifest as an intoeing gait and is commonly associated with congenital metatarsus varus, genu valgum, or femoral anteversion. Lateral tibial torsion is less common than medial rotation and is often associated with a calcaneovalgus foot. It can be compensatory to persistent femoral anteversion and idiopathic or secondary to a tight iliotibial band [3,13,14]. Physical examination, X-ray, ultrasound, CT scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used in the clinical setting to identify the causes of tibial torsion in children [15,16,17,18,19]. CT scans and MRI techniques are good imaging strategies for visually assessing the torsional profile of the tibia; however, both techniques are expensive and, in the case of CT scans, serial measurements carry with it a risk of exposing the pediatric patient to excessive radiation.

Since Staheli and his colleagues [8,20] described rotational profile, the TFA and transmalleolar axis (TMA) have been used predominantly to measure tibial torsion. Even if one study showed the validity and reliability were better the TMA than TFA compare to CT scan [21], the other study showed almost physical examinations using goniometer may not accurately reflect the tibial axis due to various posture of fibula [22], and according to Kim et al. [23], there is a low correlation between CPE and CT measurements.

A TMA measurement is difficult because it is difficult to set the mid-point of each medial and lateral malleolus of the ankle in physical examination, and it may vary depending on the measurement posture of the patient in the sagittal and transverse plane, i.e., the overall measurement may not accurately reflect the rotational profile of the tibia. So, the most popular clinical method for evaluating tibial torsion is by measuring the TFA with the child lying prone [8,20,24]. A TFA measurement is easier than the TMA in the physical examination, and we wanted to see if consistency in serial measurements could be obtained that it was more valid and reliable in comparison with the CT scan. For this reason, we chose TFA, taking into account factors such as ease of use, cost, safety, and availability. The TFA between the axis of the foot and the axis of the thigh should be measured with the child lying prone, knees flexed to 90°, and ankle neutral. The thigh axis is a line from the ischial tuberosity through the mid-point of the popliteal fossa, and the foot axis is a line from mid point of heel through second web space. Intoeing angles are given negative values while out-toeing angles are given positive values. The angle describes the status of the tibial torsion [8,24,25].

Periodic observations of the tibial torsion should be done to see if problems resolve on their own or worsen with time. Ideally, these TFA measurements should be reproducible and easy enough to be done properly by inexperienced physicians. Also, most studies of normal TFA measurements have been conducted in Western countries rather than the Far East region or in Korea. Future large-scale studies will need to take into account racial differences and a comprehensive examination will need to be done, i.e., the study method and instruments used by examiners to reduce errors in measurement values will have to be assessed during such an investigation. The aim of this study was to develop a measurement instrument that could improve the validity, inter-test and interpersonal reliabilities in TFA measurements performed on performed for children with the tibial torsion.

In this study, a less experienced examiner showed an error in repeated measurement could obtain similar value with the P-TFA when measuring the TFA with TFS; also, both inter-test and inter-personal reliability of all examiners increased with TFS. As described above, this study suggests a way to compensate for the low reproducibility and accuracy which is the fault of the classical physical examination, shows that the validity and reliability of physical examination are increased with TFS.

Accurate and reproducible TFA and TMA measurement values cannot be obtained if the knee joint cannot be kept at a 90° angle or if there is internal or external rotation of the hip joint. Thus, these changes in the position of the sagittal and transverse plane may generate measurement errors during repeated measurements. To solve this problem, the knee joint was kept bent at an angle of 90o by the main board of the TFS, internal and external rotation of hip was fixed after the wing was adjusted to left and right sides according to the sliding rod in order to measure the TFA in a more accurate position. Thus, it was possible to decrease the measurement error and the reproducibility was increased by measuring the TFA with TFS. Periodic follow-up examinations in an outpatient clinic facilitated the collection of data to be used in a future large-scale study.

Limitations of the study are that we enrolled a small number of patients in the study and that the validity was based on the TFA on the photo. Considering these limitations, a follow-up study should include more pediatric patients. Also, it is desirable to conduct a study to compare the imaging study, such as ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI.

In conclusion, TFS, which is a newly designed instrument developed for TFA measurement performed on children with intoeing and out-toeing gaits, may be more helpful to less experienced examiners.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project (No. A091220) of the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Jang SH, Woo BS, Park SB, Lee SG. Relationship between femoral anteversion and tibial torsion in intoeing gait. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 1999;23:390-396.

2. Kumar SJ, MacEwen GD. Torsional abnormalities in children's lower extremities. Orthop Clin North Am 1982;13:629-639. PMID: 7099592.

3. Sass P, Hassan G. Lower extremity abnormalities in children. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:461-468. PMID: 12924829.

4. Fabry G, Cheng LX, Molenaers G. Normal and abnormal torsional development in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;(302): 22-26.

5. Butler-Manuel PA, Guy RL, Heatley FW. Measurement of tibial torsion: a new technique applicable to ultrasound and computed tomography. Br J Radiol 1992;65:119-126. PMID: 1540801.

6. Clementz BG, Magnusson A. Assessment of tibial torsion employing fluoroscopy, computed tomography and the cryosectioning technique. Acta Radiol 1989;30:75-80. PMID: 2914121.

7. Jakob RP, Haertel M, Stussi E. Tibial torsion calculated by computerized tomography and compared to other methods of measurement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1980;62-B:238-242. PMID: 7364840.

8. Staheli LT, Corbett M, Wyss C, King H. Lower-extremity rotational problems in children. Normal values to guide management. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985;67:39-47. PMID: 3968103.

9. Rethlefsen SA, Healy BS, Wren TA, Skaggs DL, Kay RM. Causes of intoeing gait in children with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:2175-2180. PMID: 17015594.

11. Kim SI, Park SB, Lee KM. Measurement of femoral anteversion using 3 dimensional imaging technique. J Korean Soc Picture Archiving Commun Syst 1995;1:53-58.

12. Arnold AS, Komattu AV, Delp SL. Internal rotation gait: a compensatory mechanism to restore abduction capacity decreased by bone deformity. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:40-44. PMID: 9003728.

14. Lincoln TL, Suen PW. Common rotational variations in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2003;11:312-320. PMID: 14565753.

15. Kim SS, Kim SK. Derotational osteotomy and external fixation for increased femoral anteversion. J Korean Orthop Assoc 2004;39:361-365.

16. Kwon OY, Tuttle LJ, Commean PK, Mueller MJ. Reliability and validity of measures of hammer toe deformity angle and tibial torsion. Foot (Edinb) 2009;19:149-155. PMID: 20161156.

17. Hernandez RJ, Tachdjian MO, Poznanski AK, Dias LS. CT determination of femoral torsion. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1981;137:97-101. PMID: 6787898.

18. Kitaoka HB, Weiner DS, Cook AJ, Hoyt WA Jr, Askew MJ. Relationship between femoral anteversion and osteoarthritis of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:396-404. PMID: 2732318.

19. Murphy SB, Simon SR, Kijewski PK, Wilkinson RH, Griscom NT. Femoral anteversion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:1169-1176. PMID: 3667647.

21. Lee SH, Chung CY, Park MS, Choi IH, Cho TJ. Tibial torsion in cerebral palsy: validity and reliability of measurement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2098-2104. PMID: 19159112.

22. Milner CE, Soames RW. A comparison of four in vivo methods of measuring tibial torsion. J Anat 1998;193(Pt 1): 139-144. PMID: 9758144.

23. Kim HD, Lee DS, Eom MJ, Hwang JS, Han NM, Jo GY. Relationship between physical examinations and two-dimensional computed tomographic findings in children with intoeing gait. Ann Rehabil Med 2011;35:491-498. PMID: 22506164.

24. Fabry G. Normal and abnormal torsional development of the lower extremities. Acta Orthop Belg 1997;63:229-232. PMID: 9479773.

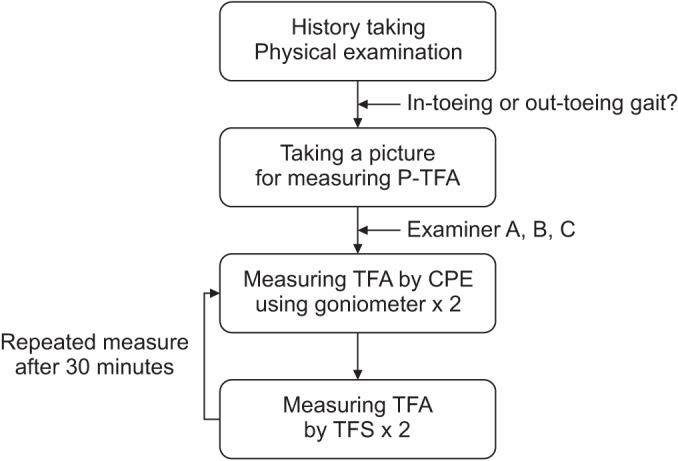

Fig. 3

Flow chart of clinical measurement. P-TFA, photographic-thigh-foot angle; CPE, classical physical examination; TFS, Thigh-Foot Supporter.

Fig. 4

Measurement of photographic thigh-foot angle (P-TFA) and thigh-foot angle (TFA) using Thigh-Foot Supporter (TFS). Lying in the prone position keeping knee joint at 90°, the ankle joint in neutral, the sole of the foot in the parallel to the floor. Then we took photos to show both thighs and feet (A). TFA was measured fixing the tibia at 90° in the sagittal and transverse plane with moving the wing of TFS (B, C).

Fig. 5

Inter-test reliability of examiner A and inter-personal reliability. Inter-test reliability: (A) TFA by CPE of examiner A and (B) TFA by TFS of examiner A. Inter-personal reliability: (C) TFA by CPE and (D) TFA by TFS. TFA, thigh-foot angle; CPE, classical physical examination; TFS, Thigh-Foot Supporter.