INTRODUCTION

Feeding problems occur in 25%ŌĆō45% of typically developing children and 80% of those with developmental delays due to chronic medical conditions [

1,

2]. Increased survival of sick and preterm infants may be associated with long-term medical and developmental problems, such as feeding difficulties in children and emotional problems in families [

3,

4].

Children with feeding difficulties usually have coexisting medical, behavioral, psychological, and developmental problems; these conditions rarely function singly or independently. Berlin et al. [

5] reported that 48%ŌĆō85% of children with feeding difficulties have 2 more conditions (developmental, behavioral, and/or medical). Moreover, Benoit et al. [

6] assessed the efficacy of behavioral interventions in eliminating the need for enteral tube feeding in infants compared with only nutritional treatment and found success among 47% of the 32 subjects in the behavioral group. Burklow et al. [

7] presented a classification system for complex pediatric feeding disorders and proposed that feeding problems occur because of interactions between biological and behavioral factors. Rommel et al. [

8] reported that children with gastrointestinal problems have a variety of oropharyngeal dysfunctions and children with heart disease have abnormal tactile responses. In addition, isolated neurological disorders are correlated with oral motor problems. However, few studies have shown the relationships between medical conditions and feeding disorders in medically complicated children.

A better understanding of the relationships between feeding disorders and their underlying medical diseases will aid in timing effective interventions for children with feeding difficulties. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the overall profile of children with feeding disorders and their relationships to medical conditions in an outpatient feeding clinic of a tertiary hospital.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides the demographic characteristics of children with feeding difficulties and describes the complex nature of feeding disorders in these children. These results will be very informative for clinicians in providing proper diagnoses and interventions to children with feeding disorders.

Approximately half of our subjects were younger than 15 months of age, which corresponded to the results of a study by Rommel et al. [

8]. Growth faltering was the primary cause of the visit to the feeding clinic in children younger than 2 years of age, whereas picky eating was the major cause in children older than age 2. Food refusal and food selectivity typically appear during feeding method transitions such as from bottle to spoon feeding and acquisition of the self-feeding skill [

11], and the prevalence of picky eating increases to 50% at 19ŌĆō24 months of age [

12]. Children between 6 months and 3 years of age are negotiating between autonomy and dependence on their parents [

13]. The growth of a child's oral motor structure occurs at around 24 months to provide proper chewing skills [

14], and children are gradually introduced to solid and viscous textured foods. If a child has difficulty processing food, it can result in oral hypersensitivity and oral-motor dysfunction [

15,

16].

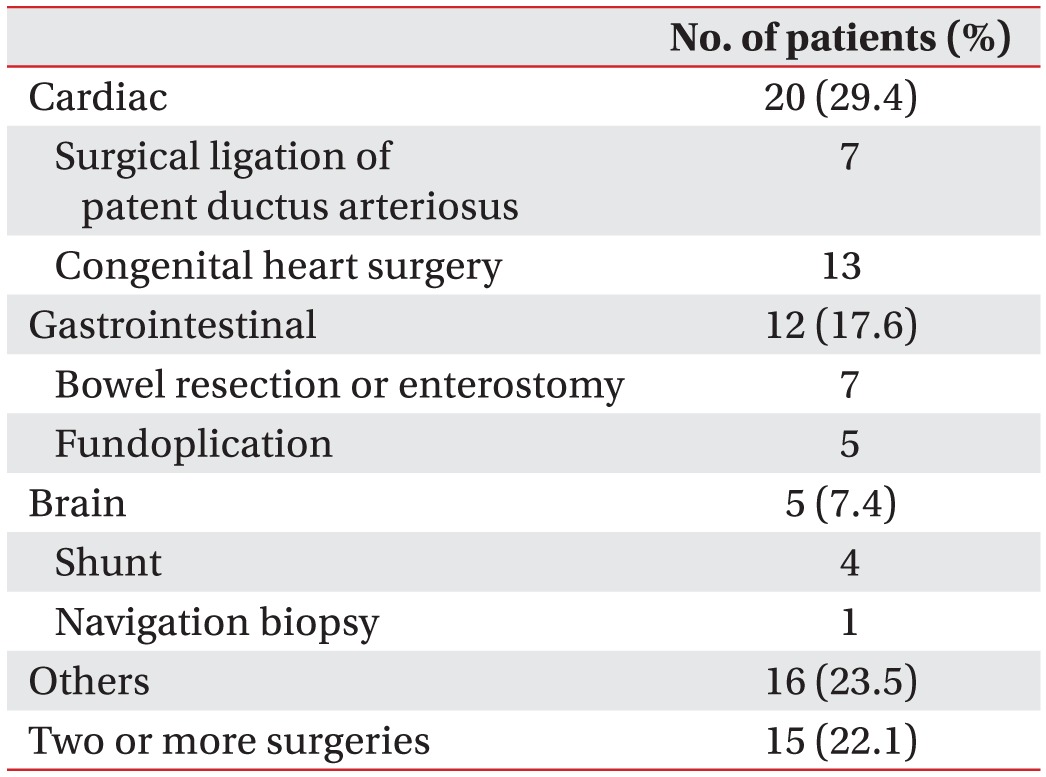

In the present study, 47.6% (68/143) of children had undergone 1 or more surgeries. Food refusal may follow a trauma to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract [

17]. Children with a history of surgery for cleft palate can develop dysphagia and learned avoidance patterns [

18], and dysphagia can appear following open heart surgery or prolonged endotracheal intubation [

19,

20]. There is intestinal rehabilitation available for patients with intestinal failure due to bowel resection that attempts to enhance the intestinal adaptive process and restore enteral anatomy [

21]. It is important to have access to surgical histories because surgery can alter feeding routes and change feeding milestones.

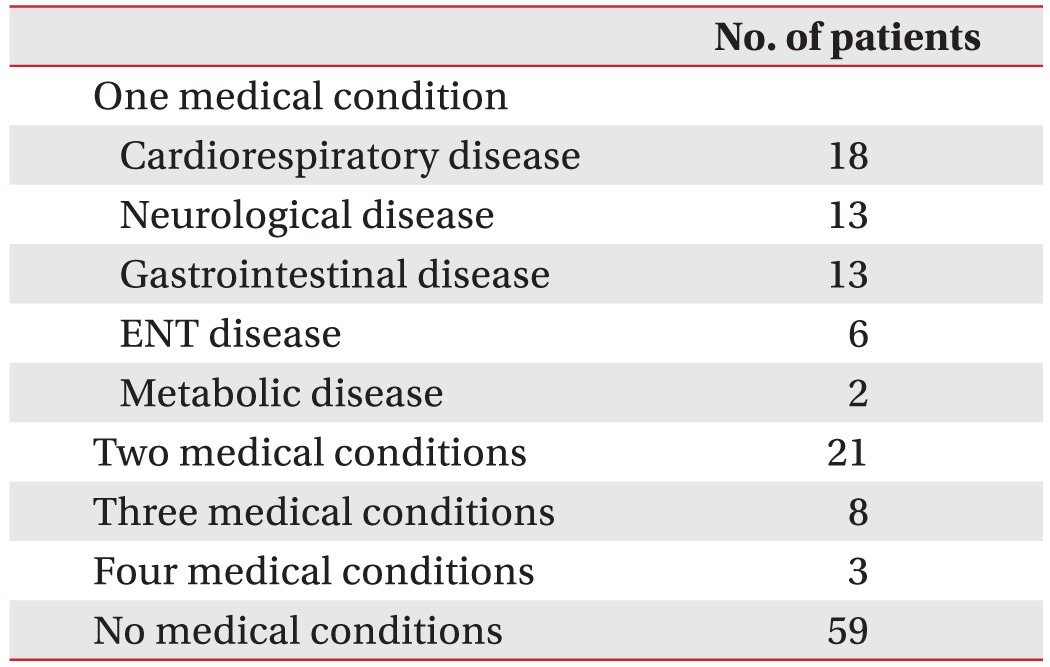

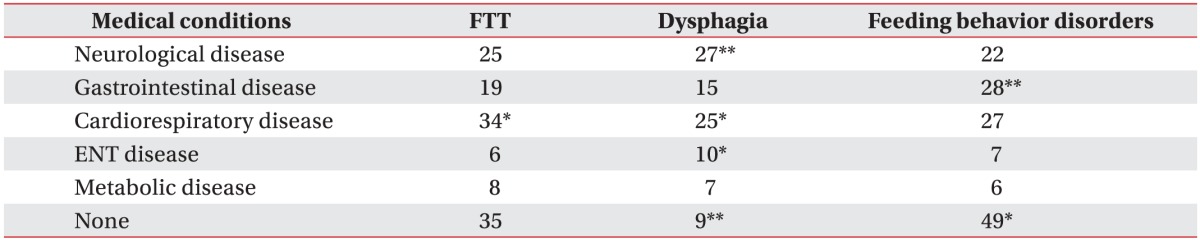

In this study, the most common medical disorder that accompanied a feeding disorder in children was cardiorespiratory disease, followed by neurological and gastrointestinal diseases. These results correspond to those of a previous study on infants younger than 1 year of age with dysphagia [

22], although Burklow et al. [

3] reported that neurological disease was the most common accompanying disease in children under 10 years of age with feeding difficulties. Furthermore, Rommel et al. [

8] reported that gastrointestinal disease was the most frequent medical diagnosis in children under age 10 who were examined for severe feeding problems. These differences between studies may result from the age ranges of the subjects enrolled, the compositions of the underlying medical diseases, or referral resources. We enrolled children under 6 years of age, and their mean age was less than that of previous studies.

Cardiorespiratory problems such as congenital heart disease and respiratory distress syndrome were significantly related to sensory food aversion in this study, and this finding is consistent with those of a previous study [

8]. Complicated and coordinated sucking, swallowing, and breathing skills are required for children to feed orally [

23], and it is possible that children with cardiorespiratory compromise tend to have difficulties with well-coordinated suck-swallowing-breathing patterns, which may lead to aspiration, limited oral intake, and impaired sensory processing of food [

24]. Medical conditions associated with inadequate caloric absorption (e.g., chronic diarrhea and metabolic disorders) or excessive caloric expenditure (e.g., hyperthyroidism and cleft lip and palate) may result in FTT [

9]; however, only cardiorespiratory conditions were statistically related to FTT in this study. This finding may be attributed to the high ratio of children with cardiopulmonary disease and the result of comprehensive nutritional support team work in our hospital. Growth failure in children with cardiorespiratory disease is related to poor feeding, increased metabolic rate, malabsorption, and breathlessness [

25]. Therefore, early comprehensive feeding evaluation and intervention are recommended for children with cardiorespiratory disease, particularly in those who have undergone major surgery. Nutrition counseling is critical, and programs for parents can also be developed to reduce children's sensory defensiveness with regard to the textures, tastes, temperatures, and smells of new foods.

Various feeding behavior disorders have been reported in children with medical diseases, and Kerzner et al. [

26] suggested that it is necessary to pay attention to behavioral symptoms and signs to recognize feeding difficulties; It is important to identify behavioral red flags such as food fixation (selective, extreme dietary limitations), noxious (forceful and/or persecutory) feeding, abrupt cessation of feeding after a triggering event, anticipatory gagging, and FTT. In this study, 65.5% (55/84) of children with a medical condition also had 1 or more feeding behavior disorders, and one study reported that the presence of a medical condition did not exclude the effects of considerable behavioral components in 85% of children who presented with feeding difficulties [

7]. Complex feeding problems require that clinicians carefully recognize a variety of components, including developmental and feeding history, medical conditions, emotional status, and nutrition. Through this approach, it is possible to identify the origin of a feeding problem and promote the most effective treatment plan [

27].

Notably, we found no underlying medical disorder to explain the feeding disorders in 59 (41.3%) of the 143 subjects; many of these children had feeding behavior disorders such as sensory food aversion and infantile anorexia with FTT. This group of patients is part of the majority in our feeding clinic (FTT-feeding behavior disorders, 41.1%). Although transient picky eating may be normal in children and disappear following development [

28], special attention should be given to prevent overlooking detrimental effects to a child's early development. Children with nonorganic FTT and a feeding problem have more sensory processing difficulties and delays in cognition, motor skills, and language development compared with those of age-matched controls [

29].

In addition, we observed that 9 children with no medical condition had dysphagia, which we defined as a chewing and swallowing problem based on reports that included coughing, increased work of breathing, history of aspiration pneumonia, and/or abnormal results of a videofluoroscopic swallowing study. These children had difficulties chewing and moving solid food to the oropharynx or esophagus during the transition from liquid to solid feeding, and this result suggests that the causes of dysphagia may include not only medical diseases such as neurological or structural abnormalities but also psychogenic or unknown factors [

30].

Ninety-three patients (65.0%) met the criteria for any combination of 2 or more of a feeding behavior disorder, dysphagia, or FTT. Managing children with feeding difficulties may vary depending on the clinical setting and the training backgrounds of the medical personnel. For instance, pediatric gastroenterologists focus on diagnosing possible organic dysfunction and assessing nutritional status [

26,

31], pediatric psychologists play a major role in treating patients with feeding behavior disorders and in the interactions between caretakers and children, and physiatrists are more attentive to diagnosing and managing oropharyngeal dysphagia. Therefore, the complex nature of feeding disorders in children requires a multidisciplinary team approach.

A number of limitations of this study should be mentioned. Because the data were collected retrospectively from a single feeding clinic in a tertiary hospital, our findings do not necessarily represent the wide spectrum of children with feeding difficulties. Moreover, many other important aspects of feeding disorders including child-parent interactions and development were not explored. In addition, although our study suggested that it is important to have access to surgical histories, our data were insufficient for analyzing any relationships between surgery history and feeding disorders because the types of surgery varied and our sample was somewhat small. A prospective study that includes more detailed evaluations of nutrition, sensory defensiveness, oral motor function, development assessment, and age-appropriate feeding skills is needed in children with feeding disorders.

In conclusion, a multidisciplinary team approach is proposed to comprehensively evaluate and treat children with feeding difficulties because combinations of feeding problems are very common among children. This overall profile will provide clinicians with a clear understanding of the complexity of feeding disorders in children and their relationships with various medical conditions.