- Search

| Ann Rehabil Med > Volume 40(4); 2016 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

To describe the longitudinal characteristics of unintentional fall accidents using a representative population-based sample of Korean adults.

Methods

We examined data from the Korean Community Health Survey from 2008 to 2013. Univariate analysis and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify the characteristics of fall accidents in adults.

Results

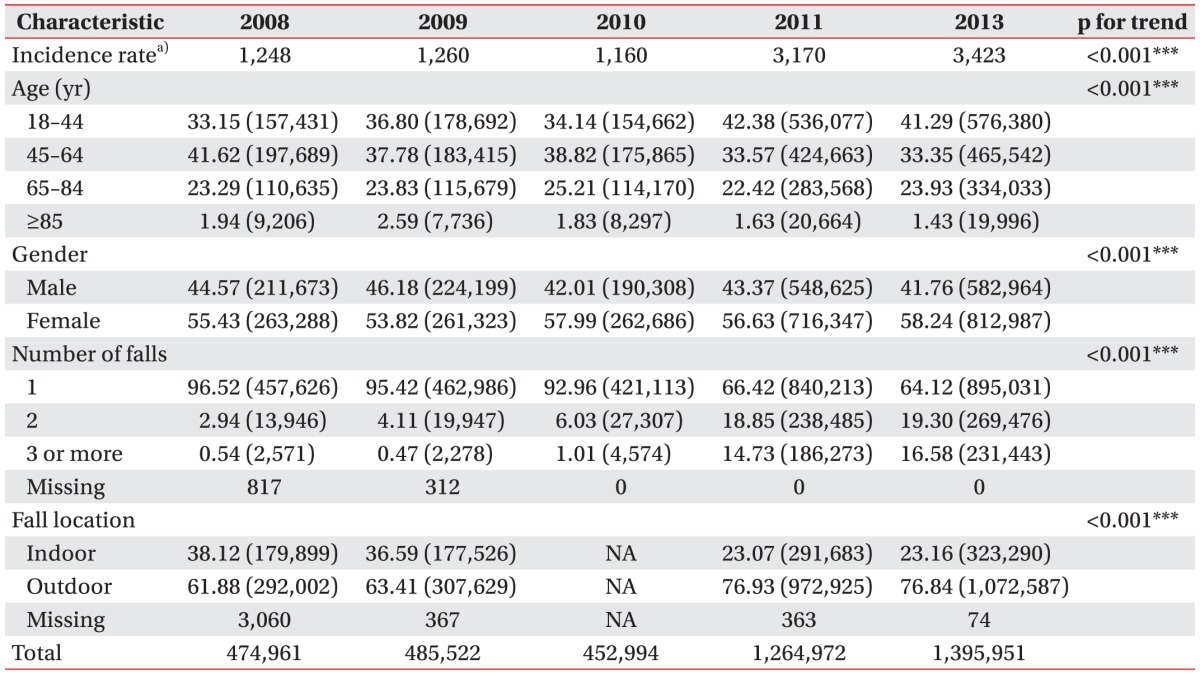

Between 2008 and 2013, the incidence rate of fall accidents requiring medical treatment increased from 1,248 to 3,423 per 100,000 people (p<0.001), while the proportion of indoor fall accidents decreased from 38.12% to 23.16% (p<0.001). Females had more annual fall accidents than males (p<0.001). The major reason for fall accidents was slippery floors (33.7% in 2011 and 36.3% in 2013). Between 2008 and 2010, variables associated with higher fall accident risk included specific months (August and September), old age, female gender, current drinker, current smoker, diabetes, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and depression. A high level of education and living with a partner were negatively associated with fall accident risk. In 2013, people experiencing more than 1 fall accident felt more fear of falling than those having no fall accidents (odds ratio [OR] for 1 fall, 2.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.04ŌĆō2.12; OR for more than 2 falls, 2.97; 95% CI, 2.83ŌĆō3.10).

In Korea, the cause-specific death rate of fall accidents was 4.6 per 100,000 people in 2013, a rate even higher than for breast cancer, sepsis, and tuberculosis (4.4, 4.3, and 4.1) [1]. As falls are the third highest non-disease cause of death in Korea, it is critical to have a better understanding of fall accident trends. Since 2008, the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) have conducted an annual national health survey, the Korean Community Health Survey (KCHS), which covers a wide variety of health topics, including extensive information regarding falls [2].

Unfortunately, although the nationwide survey data has been available to the public, most Korean research papers cite foreign studies to describe the incidence of falls in Korea [3,4,5], and the information about falls from the cited Western studies is often outdated [6,7]. Several studies have reported incidence rates in Korea; however, the results were not consistent due to varying sample size, small resident area, a specific target population, and differing methodological approaches [3,4,5,8]. For example, an observational study randomly recruited 335 community-dwelling older adults from a cohort study and reported that 15% of their sample had experienced falls. In contrast, a prospective study reported a high fall occurrence of 41.6% when they conducted personal interviews in a small city with 260 community dwelling older adults [4].

Since 2008, the KCDC has annually reported summary statistics of the KCHS, including falls [9,10]. In addition, a recent study used the 2011 KCHS to report the prevalence of falls [11]. However, the minimally descriptive report is limited to single annual fall information only [10,11]. It is unclear whether the trends of falls among community dwelling adults have been consistent or varied dramatically in consecutive years in Korea, because few studies have been conducted using national data to examine falls over extended time periods.

An investigation of a series of national level datasets may provide important information about the general trends in fall accidents in Korea. The general trends will outline the change in relationships between fall accidents and demographic characteristics and environmental factors for consecutive years. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the incidence rates of fall accidents and the characteristics of people who experienced falls during a 7-year period (2008ŌĆō2013) in South Korea.

This study utilized data from the annual national health survey, the KCHS, from 2008 to 2013 [2]. This dataset represents populations of community dwelling Korean adults aged 19 years and older. The data was collected in 253 community units consisting of 16 metropolitan cities and provinces [2]. The samples in the KCHS were extracted based on two stratified sampling procedures. In the first stage of sampling, the primary sampling units were selected according to the resident area (i.e., cities and type of households). In the second stage of sampling, the number of households was selected based on the size of the identified resident areas and the proportional composition of educational attainment of family members in the household. The sampling methods ensured that the samples of the KCHS would be representative of the entire Korean population. Trained surveyors visited the selected households and conducted face-to-face interviews using computer assisted personal interviewing.

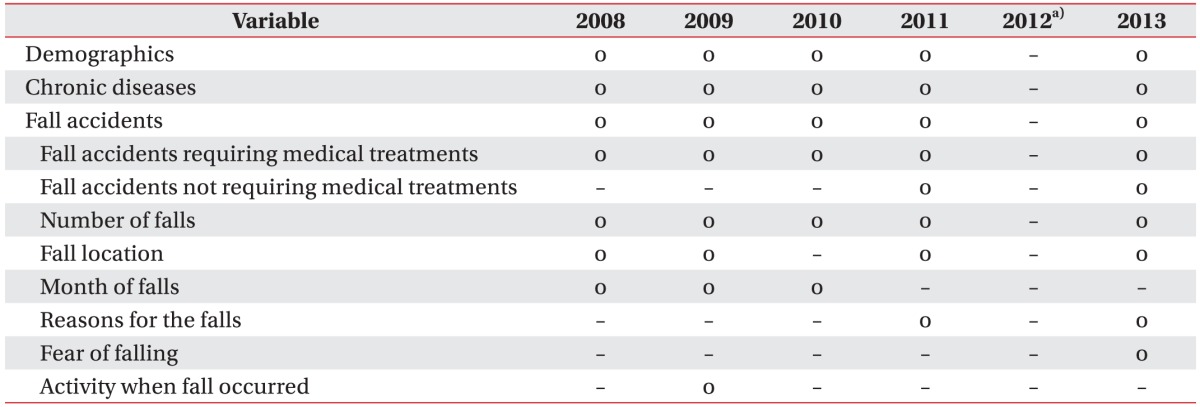

The KCHS covers various health topics: basic demographics, health behaviors (smoking, drinking, and exercise), mental health, chronic diseases, quality of life, accidents (i.e., car accidents, falls, etc.), and nutrition. Since 2008, fall accidents and related information were collected in the survey (Table 1).

The 2012 KCHS did not include the questions about falls, and, thus fall statistics in 2012 are not reported in this paper. The KCHS contained longitudinal descriptive statistics, such as the incidence rates of falling requiring medical treatment, reasons for falls, and locations of falls for at least 2 of the 5 consecutive years.

Fall accidents were not consistently defined across the 2008ŌĆō2013 KCHSs. For the purpose of this study, we defined a fall accident as a fall that required medical treatment in the 12 months immediately following, and the definition of fall accidents was used for all analyses. The participants were asked a series of questions related to fall accidents (see Table 1), such as "Have you experienced at least 1 fall accident that required medical treatments in the last 12 months? A fall accident may include slipping, tripping or stumbling." All subjects gave written informed consent before completing the KCHS, and the Institutional Review Board of the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (No. 2013-06EXP-01-3C) approved this study.

All test results were weighted to represent the Korean adult population. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, were used to describe the characteristics of data. Longitudinal incidence rates of fall accidents (per 100,000) requiring medical treatments were calculated from 2008 to 2013. The Cochran-Armitage trend test was used to examine the trends of fall accidents with 2 levels of categorical variables, including sex and fall location. Chi-square tests were used to test the trends of fall accidents with more than 2 levels of categorical variables, including age group and number of falls [12]. Pearson correlation was used to test the relationship between the trends of fall accident occurrence and the location proportions of these fall accidents for 7 years. We performed multivariable logistic regression to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) in order to identify the risk factors for fall accidents and fear of falls. In logistic regression models, we included covariates, including demographics and chronic conditions, which were identified from previous community-based studies [4,5,11,13]. Statistical significance was determined at the 0.05 level, and results were expressed with a 95% confidence interval (CI). All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for complex survey designs.

The sample sizes of the data were 220,258 in 2008, 230,715 in 2009, 229,229 in 2010, 229,226 in 2011, and 228,781 in 2013. Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of the study participants who experienced at least 1 fall accident that required medical treatment during the last 12 months in each year. Females had more fall accidents than males in each year (p<0.001). The proportion of females who experienced fall accidents gradually increased across the 5-year datasets (53.43% in 2008 to 58.24% in 2013; p<0.001).

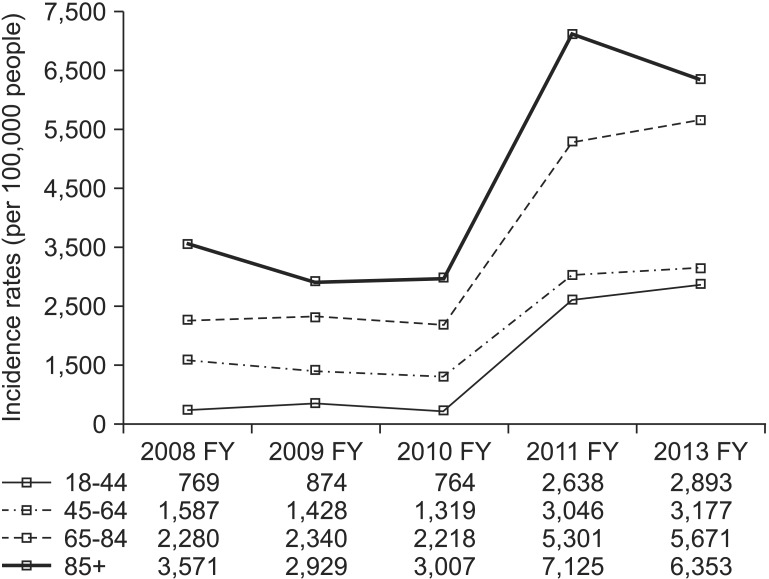

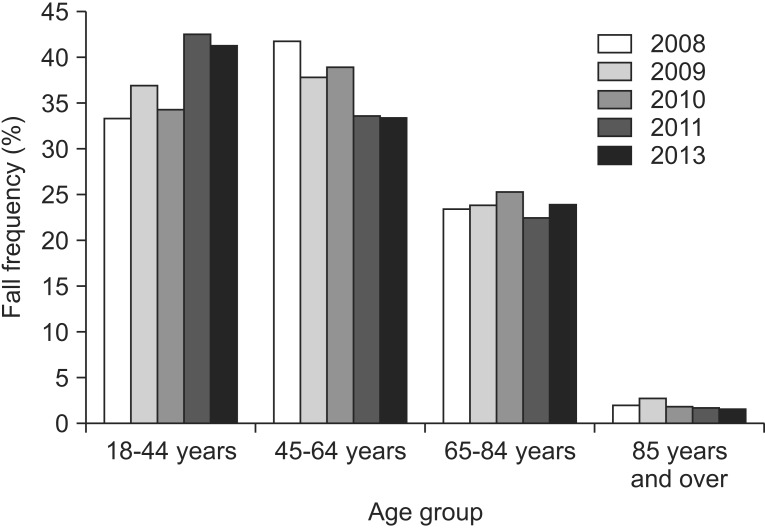

Fig. 1 presents the trends of fall accidents in age groups across the consecutive years. Fall accidents in adults between the ages of 18 and 44 years rapidly increased between 2010 and 2011 (p<0.001). Fall accidents in adults between the ages of 45 and 65 years old consistently decreased, except for 2010 (p<0.001). Fall accidents in adults over 85 years old gradually decreased, except in 2009 (p<0.001). Fall accidents in adults between the ages of 65 and 84 years rapidly decreased between 2010 and 2011 (p<0.001). Since 2008, the incidence rates (per 100,000 people) of falls increased significantly (p<0.001), and the incidence rate in 2013 (3,423 per 100,000 people) was 2.74 times of the incidence rate in 2008 (1,248 per 100,000 people). Fig. 2 presents the incidence rates among age groups across consecutive years. Old age groups demonstrated high incidence rates compared to young age groups, figures not shown. At the same time, the percentage of indoor fall accidents also consistently decreased from 31.12% in 2008 to 23.16% in 2013 (p<0.001). The correlation between the incidence rates and proportion of indoor fall accidents, and the correlation between the incidence rates and proportion of outdoor fall accidents in 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2013 showed strong relationships (r=ŌłÆ0.99, p=0.007 and r=0.99, p=0.007, respectively). Table 2 presents a significant increase in the number of individuals experiencing more than 2 fall accidents, from 4.09% in 2011 to 33.17% in 2013 (p<0.001). In 2009, people experienced fall accidents while performing basic daily activities (55.58%), working (21.28%), other activities (7.29%), exercise (7.33%), social activities (4.50%), playing (3.02%), and studying (0.98%).

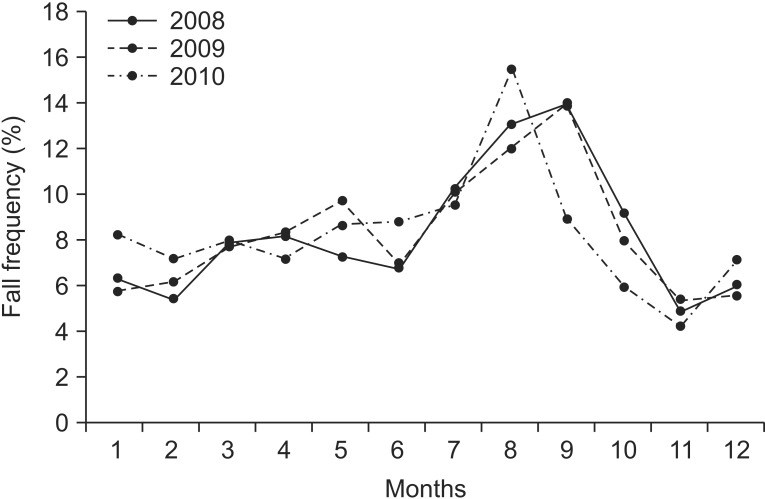

The major reason for fall accidents was slippery floors (33.7% in 2011 and 36.3% in 2013), with additional reasons including the following: making a false step (19.8% in 2011 and 19.1% in 2013), caught in a footpath or the threshold (11.1% in 2011 and 12.4% in 2013), felt dizzy or falling unconscious (11.04% in 2011 and 11.5% in 2013), hit by people or objects (10.4% in 2011 and 9.7% in 2013), other people caused the fall (9.7% in 2011 and 6.7% in 2013), steep slopes (3.5% in 2011 and 3.2% in 2013), and poor lighting (0.9% in 2011 and 0.6% in 2013). Most fall accidents occurred in August and September in 2008, 2009, and 2010.

Fig. 3 presents the frequency of fall accidents across a 12-month period between 2008 and 2010. The overall fall accident frequency for the 3 consecutive years demonstrated similar trends. Fall accidents increased in July and reached the highest fall accident frequency in August and September. Fall accidents decreased in October and reached the lowest frequency in November.

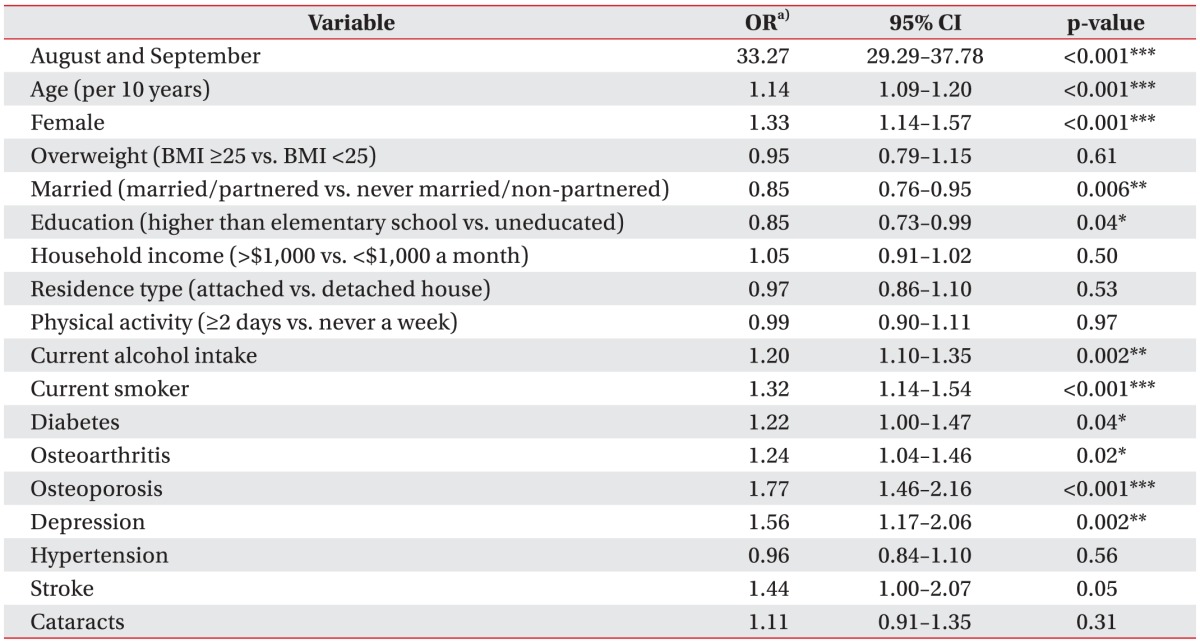

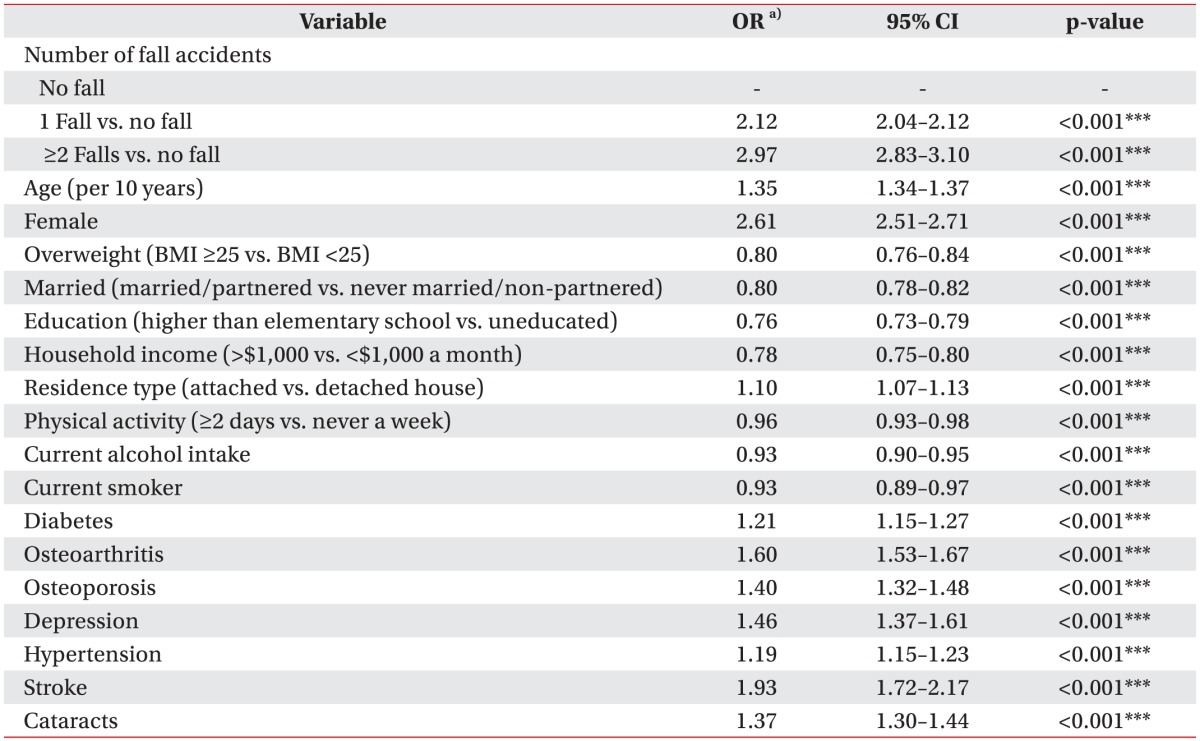

Table 3 represents the multivariable logistic regression analysis of the risk of fall accidents in the most recent dataset of 2010. The following multivariable-adjusted ORs predicted a higher risk of fall accidents: in specific months (OR for August and September, 33.27; 95% CI, 29.29ŌĆō37.78), older age (OR per 10 years, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09ŌĆō1.20), female gender (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.14ŌĆō1.57), current alcohol intake (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.10ŌĆō1.35), current smokers (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14ŌĆō1.54), and in people with diabetes (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00ŌĆō1.47), osteoarthritis (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04ŌĆō1.46), osteoporosis (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.46ŌĆō2.16), and depression (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.17ŌĆō2.06). Being married (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.76ŌĆō0.95) and having a higher education (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.73ŌĆō0.99) were associated with a lower risk of fall accidents while being overweight, household income levels, residence type, physical activity, stroke history, and cataract history were not associated with a risk of any fall accidents in the past 12 months. The interaction effects between the specific month (August and September) and the rest of variables was also investigated. The specific month demonstrated the interaction effects with age (OR per 10 years, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04ŌĆō1.21), female gender (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21ŌĆō1.96) and physical activity (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58ŌĆō0.92). The risk factors of experiencing multiple fall accidents were higher in people with cataracts (OR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.37ŌĆō5.52) and in current smokers (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.15ŌĆō3.74) by more than 2 times; however, increased age (per 10 years) was associated with a low risk of multiple fall accidents compared to people between the ages of 18 and 29 years (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.52ŌĆō0.77). Table 4 presents the multivariable logistic regression model for the risk of fear of falls in 2013. People who experienced 1 fall accident (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 2.04ŌĆō2.12) and who had more than 2 fall accidents (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 2.83ŌĆō3.10) felt more fear of falls than those who had no fall accident experience within the last 12 months. Older adults, females, attached house dwellers (apartment or town house), or a presence of diabetes, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, depression, hypertension, stroke, and cataracts were also associated with a higher risk of fear of falls. In contrast, people who were overweight, married, highly educated, wealthier, physically active, current alcohol intake, and current smokers had a lower risk of fear of falling.

We have identified the trends regarding fall accidents in Korean adults between 2008 and 2013 and found that fall accidents requiring medical treatments had increased over time. Adult females between 64 and 85 years old were more likely to experience fall accidents. The number of outdoor fall accidents and the number of adults having more than 2 fall accidents have increased over time. Variables associated with fall accident risks included specific months (August and September), age (10 years), female gender, current alcohol intake, current smoker, diabetes, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and depression. The major reason for fall accidents was slippery floors, and when people had fall accidents, they understandably expressed more fear of falling than those who had had no fall accidents.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the trends of fall accidents using a nationally representative sample of Korean adults for consecutive years. Although a previous study investigated risk factors of fall accidents using a national level dataset, the results were limited to a specific year and a population aged 65 years or older [11]. On the other hand, by analyzing the trends of fall accidents in various demographics and environmental characteristics for a consecutive 3-year period, we identified that seasonal changes, especially in August and September, was the major factor for fall accidents (25.2% of falls). The seasonal change was previously an unknown risk factor for fall accidents, in contrast with age, which was the major risk factor of fall accidents identified by previous Korean and Western studies [11,14]. The seasonal change demonstrated interaction effects with age (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04ŌĆō1.21), female (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21ŌĆō1.96), and physical activity (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58ŌĆō0.92) indicating that adults over 30 years old experienced (per 10 years) 12% increased odds of fall accidents and females have a greater than 20% increased risk of fall accidents in August and September in 2010.

We were not able to test the interaction effects between the seasonal change and outdoor fall accidents with logistic regression models because the 2010 dataset did not contain the outdoor fall accident variable and there were considerable missing data in the outdoor fall accident variable in other available datasets, such as 96% missing data in 2008 and 95% missing data in 2009. Instead, we used chi-square tests for the interaction effects between seasonal change and the outdoor fall accident variable using the 2008 and 2009 dataset. In both datasets, there were significant relationships between outdoor fall accidents and seasonal change (p<0.001). However, as the results were not adjusted for other demographics and covariates, further studies are needed to test the interaction effects between outdoor fall accidents and seasonal change.

During these same months, among people who reported being regularly physically active (more than 2 days), the risk of falling was 27% lower compared to those who were never physically active. However, the fall accident frequencies across month are not consistent with previous studies [8,15]. In our study, most adults over 65 years old had fall accidents in August (16.6%). A prospective study reported that older adults frequently had falls in April (12.8%) and December (11.7%) [8]. A community-based study found that 38.9% of falls occurred between March and May [15]. Although the differences could be influenced by recall bias, a particular sub-population, and loss of memory in older adults, our findings were consistent for 3 consecutive years from 2008 to 2010.

The increasing fall accidents in Korea may be explained by environmental factors, such as lifestyle changes across the nation. Korea has experienced remarkable socioeconomic growth that has resulted in significant changes in nutrition, leisure, and lifestyle [16]. For example, 48% of Koreans spent more than 3 hours of leisure time on weekends in 2011, and 61% of people reported spending the same amount of leisure time in 2013 [17]. In 2012, Koreans enjoyed more outdoor leisure activities (58.0%) than indoor activities (41.9%) [18]. Our findings also suggested that the lifestyle changes are associated with increasing fall accidents (r=0.99, p=0.007), and the proportion of outdoor falls has increased from 68.9% in 2008 to 76.8% in 2013.

Our finding that females had more fall accidents than males is consistent with previous Korean and Western studies [4,11,14,15]. The differences in muscle strength levels may contribute to the high rate of falls in women. The loss of lower body strength is strongly associated with increasing risk of fall accidents [19,20]. Previous Western studies have suggested that men have greater lower body strength than women [19,20,21] and, thus, males were at a relatively lower risk of falls compared to women. Unfortunately, the KCHS is based on interviews and does not include physiological measures, such as muscle strength, difference in gate, or knee action; therefore, we were not able to test the gender difference in relation to physiological functions. A possible explanation is that a high risk of falls in women was associated with osteoporosis [22]. Our finding supports the fact that women were at a higher risk of osteoporosis than men (OR, 8.28; 95% CI, 7.33ŌĆō9.36). However, future research is needed to clarify the relationship between gender difference and risk of fall accidents.

Between 2008 and 2013, the proportion of people experiencing more than 2 fall accidents in a 12-month period has consistently increased, and people suffering more than 2 fall accidents felt more fear of falling than non-fallers (OR, 2.97; 95% CI, 2.83ŌĆō3.10). A previous study suggested that 46% of healthy older people were afraid of falling, and 56% of them curtailed daily activities due to their fear [23]. Reduced physical capacity can also increase the risk of falls [19,20]. Thus, with the trend of multiple fall accidents increasing along with their fear of falling, community dwelling Korean people are expected to be at a greater risk of potential falls than previously.

Various fall prevention programs showed their effectiveness at preventing fall accidents, such as multiple-component group exercise, assessment and multifactorial intervention, and home modification [24]. Also, various fall prevention programs and interventions have been established in Korea [25]. Despite these efforts, the fall incidence rate has increased since 2008. Fall accidents can cause severe injuries (or even death), as well as causing an increased social burden [1]. As the Korean population ages, fall accidents are expected to increase. Due to the multifactorial characteristics of effective fall prevention programs (i.e., general medical assessment focusing on fall risks, fall history, medication intake, and the use of assistive devices) [26], individuals may not benefit from a fall prevention program without comprehensive social support. Thus, Korean society may need to establish a systematic social support system to prevent fall accidents.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, questions from each dataset concerning fall accidents and related information were not consistent each year, except for the number of fall accidents. For example, between 2008 and 2010, falls were defined as having at least1 fall that required seeking medical treatment in the past year; however, since 2011, the KCHS has asked more comprehensive questions about fall accidents, both those requiring and not requiring medical treatment. In addition, some questions, such as reasons for falls, location of falls, fear of falling, and activities when falls occurred, were limited in a specific year. For these reasons, we were not able to test their trends. Therefore, the KCHS should include consistent questions about fall accidents in order to track stable trends. Secondly, the high increase in incidence rates between 2010 and 2011 could be a function of inconsistent questioning concerning fall accidents in the KCHS, such as the model of questioning regarding fall accidents. Therefore, the incidence rates after 2011 and 2013 could be inflated, compared to the incidence rates in 2008, 2009, and 2010. Finally, the KCHS does not include people in medical hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and military facilities, so the results of similar analysis among those groups may differ.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to show our gratitude to Dr. Kit N. Simpson and Dr. Craig A. Velozo for providing their research ideas and statistical consultations. The Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) supported the study and provided the study data. We retrieved the study data from the KCDC webpage (chs.cdc.go.kr).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Statistics Korea. Annual report on the cause of death statistics. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2014.

2. Kim YT, Choi BY, Lee KO, Kim H, Chun JH, Kim SY, et al. Overview of Korean community health survey. J Korean Med Assoc 2012;55:74-83.

3. Cho JP, Paek KW, Song HJ, Jung YS, Moon HW. Prevalence and associated factors of falls in the elderly community. Korean J Prev Med 2001;34:47-54.

4. Lim NG, Shim KB, Kim YB, Park JL, Kim EY, Na BJ, et al. A study on the prevalence and associated factors of falls in some rural elderly. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2002;6:183-196.

5. Shin KR, Kang Y, Hwang EH, Jung D. The prevalence, characteristics and correlates of falls in Korean community-dwelling older adults. Int Nurs Rev 2009;56:387-392. PMID: 19702815.

6. Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1701-1707. PMID: 3205267.

8. Lim JY, Park WB, Oh MK, Kang EK, Paik NJ. Falls in a proportional region population in Korean elderly: incidence, consequences, and risk factors. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2010;14:8-17.

9. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 Korean Community Health Survey. Cheongju: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

10. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Having a quick look at the regional statistics between 2008 and 2011. Cheongju: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012.

11. Choi EJ, Kim SA, Kim NR, Rhee JA, Yun YW, Shin MH. Risk factors for falls in older Korean adults: the 2011 Community Health Survey. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:1482-1487. PMID: 25408578.

13. Kim JM, Lee MS, Song HJ. An analysis of risk factors for falls in the elderly by gender. Korean J Health Educ Promot 2008;25:1-18.

14. Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2010;21:658-668. PMID: 20585256.

15. Kim JM, Lee MS. Risk factors for falls in the elderly population in Korea: an analysis of the third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Korean J Health Educ Promot 2007;24:23-39.

16. Han MA, Kim KS, Park J, Kang MG, Ryu SY. Association between levels of physical activity and poor self-rated health in Korean adults: the Third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2005. Public Health 2009;123:665-669. PMID: 19854457.

17. Korea Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism. Survey on citizen's sport participation 2013. Sejong: Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism; 2013.

18. Korea Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism. Survey on citizen's leisure participation 2012. Sejong: Ministry of Culture Sports and Tourism; 2012.

19. Stevens JA, Sogolow ED. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj Prev 2005;11:115-119. PMID: 15805442.

20. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention..

21. de Rekeneire N, Visser M, Peila R, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Tylavsky FA, et al. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:841-846. PMID: 12757573.

22. Fletcher PC, Hirdes JP. Risk factors for falling among community-based seniors using home care services. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M504-M510. PMID: 12145363.

23. Howland J, Peterson EW, Levin WC, Fried L, Pordon D, Bak S. Fear of falling among the community-dwelling elderly. J Aging Health 1993;5:229-243. PMID: 10125446.

24. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Lamb SE, Gates S, Cumming RG, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD007146PMID: 19370674.

25. Sohng KY, Moon JS, Song HH, Lee KS, Kim YS. Fall prevention exercise program for fall risk factor reduction of the community-dwelling elderly in Korea. Yonsei Med J 2003;44:883-891. PMID: 14584107.

26. Neyens JC, Dijcks BP, van Haastregt JC, de Witte LP, van den Heuvel WJ, Crebolder HF, et al. The development of a multidisciplinary fall risk evaluation tool for demented nursing home patients in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2006;6:74PMID: 16551348.

Fig.┬Ā3

Fall accident frequency across 12 months between 2008 and 2010. Most fall accidents occurred in August and September.

- TOOLS