Lipoma Compressing the Sciatic Nerve in a Patient With Suspicious Central Post-stroke Pain

Article information

Abstract

Lipomas are mostly located in the subcutaneous tissues and rarely cause symptoms. Occasionally, peripheral nerve compression by lipomas is reported. We describe a case of a 59-year-old man with a left-middle cerebral artery infarction who was newly diagnosed as right basal ganglia and thalamic intracranial hemorrhage. He had neuropathic pain in the left arm and leg that was suspected to be central post-stroke pain. The administration of pain medication brought only temporary symptom relief. Nerve conduction and electromyography studies revealed left L5 radiculopathy and he showed a positive ‘sign of the buttock’ in the left hip. Left-hip magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intermuscular lipoma compressing the sciatic nerve. After surgery, the range of motion in the left hip joint was significantly increased, and the patient's pain was relieved.

INTRODUCTION

Lipomas are common benign masses that are usually located in subcutaneous tissue and do not infiltrate surrounding tissues. They are usually asymptomatic, and nerve compression by lipomas is unusual. Intermuscular lipomas are rare and can easily be overlooked because of their uncommon location [1].

‘Sign of the buttock,’ first described by Cyriax, suggests a serious pathology in the hip and pelvis. It is a combination of restricted straight leg raise and limited passive hip flexion with a bent knee. This sign is associated with non-capsular patterns of restricted range of motion (ROM) and indicates conditions such as osteomyelitis, sacral fracture, septic arthritis, abscess, rheumatic fever with bursitis, neoplasm, and septic bursitis [2].

Central post-stroke pain (CPSP) [3], which affects 12% of patients with stroke, is centrally mediated neuropathic pain. Clinical characteristics of CPSP resemble those of peripheral neuropathic pain, so it is difficult to distinguish this type of pain from other conditions.

We report a rare case of an intermuscular lipoma compressing the sciatic nerve in the left hip associated with positive sign of the buttock in a patient with CPSP on the left side caused by right thalamic injury, together with a related literature review.

CASE REPORT

A 59-year-old man with a known left-middle cerebral artery infarction was newly diagnosed with right basal ganglia (BG) and thalamic intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Emergency external ventricular drainage was performed (Fig. 1). He was referred to our hospital for comprehensive rehabilitation. Initially, he had zero grade in the left upper and lower limbs, according to a manual muscle test, and zero grade of spasticity by the Modified Ashworth Scale. The patient's Korean version of Modified Barthel Index score was 4 points and his Mini-Mental Status Examination score was 15 points. He required maximal assistance in mobility. In addition, he had neuropathic pain symptoms, such as numbness and tingling on the left hemiplegic side, suspected to be CPSP. He especially complained about neuropathic pain in the posterior thigh and lower leg. We performed a three-phase bone scan, confirming the presence of a complex regional pain syndrome involving the left arm. We therefore added 300 mg of gabapentin three times per day to the treatment to control neuropathic pain, which improved. He was discharged from our hospital at that time.

Brain-computed tomography upon first admission showed encephalomalacic change in the right basal ganglia and thalamus caused by an intracranial hemorrhage.

He was later readmitted to our department with persistent neuropathic pain in the left leg. We increased the dose of gabapentin to 600 mg twice per day, but the treatment did not relieve his neuropathic pain. He also suffered left hip pain and restricted ROM in the hip joint with flexion of 70° and could not maintain a sitting posture for ambulation with a wheelchair.

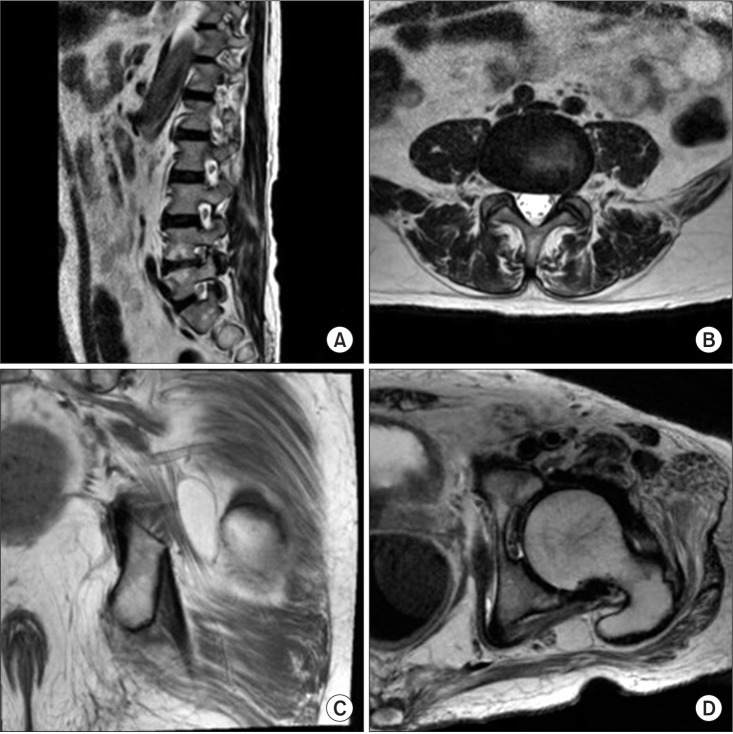

Left-hip radiography revealed an osteophyte of the left femoral head (Fig. 2). We performed a nerve conduction study (NCS) and electromyography (EMG); the findings were compatible with left L5 radiculopathy. Sensory NCS showed normal findings in both sural and superficial peroneal nerves. Motor NCS revealed slightly decreased amplitudes (by about 30%) of compound motor-action potentials in the left tibial and deep peroneal nerves relative to the right side, but showed normal onset latency and conduction velocity in those nerves. In needle EMG, tensor fascia latae, tibialis anterior, and tibialis posterior muscles showed positive sharp waves at rest. However, during the physical examination, the patient showed sign of the buttock (Fig. 3) in the left hip. We performed lumbosacral (LS) spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in addition to left-hip MRI. The LS spine MRI revealed a left foraminal protrusion at the L4-5 level that was compressing the nerve root (Fig. 4). We observed deep, soft tissue in the ischiofemoral space in the MRI of the left hip, measuring 4.0 cm×1.1 cm×2.2 cm around the sciatic nerve (Fig. 4), which we suspected to be a lipoma.

The sign of the buttock: passive hip flexion with bent knee (B) is more limited and/or painful than straight leg raising (A).

T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbosacral area showed diffuse bulging of the L4-5 disc. Sagittal view (A) and axial view (B) at L4-5 level. T1-weighted MRI of the left hip showed deep soft tissue in the ischiofemoral space, measuring about 4.0 cm×1.1 cm×2.2 cm around the sciatic nerve. Coronal view (C) and axial view (D).

The patient was referred to the orthopedics department for surgical removal of the mass. An encapsulated fatty mass, 4 cm×4 cm×2 cm in volume, was discovered between the gluteus medius and maximus muscles; it was adhering to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 5). Immediately after surgery, the patient's left hip ROM was improved up to 110° in flexion, and neuropathic pain in the left leg was alleviated. His ROM after one week showed increments of up to 120° in flexion. Consequently, he could sit upright in a wheelchair without limitations and ambulate in this fashion.

DISCUSSION

Less than 5% of lipomas compress peripheral nerves [4]. There was a previously reported case of sciatic nerve compression by intermuscular lipomas, but the patient lacked a remarkable medical history, showed weakness in the ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors, and had a huge lipoma measuring 25 cm×13 cm×8 cm, which was palpable. He was diagnosed with sciatic neuropathy in NCS and EMG. In our case, the patient had zero grade in the left side due to previous ICH. We could therefore not detect a muscle weakness involving the sciatic nerve in the left leg. He had a non-palpable lipoma. Also, NCS and EMG did not revealed sciatic neuropathy. In these respects, it was harder to identify a lipoma compressing the sciatic nerve than with the previously reported case [5]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing an intermuscular lipoma compressing a nerve in a stroke patient with CPSP.

Some factors complicated the identification of the sources of pain in the present case. First, left-hip radiography showed an osteophyte in the left femoral head, and the patient had limited passive hip internal rotation of 10°, suggesting a capsular pattern of the hip lesion, such as from osteoarthritis [2]. Second, he had a history of brain lesions involving the BG and thalamus. CPSP is characterized by pain and sensory abnormalities of affected extremities in post-stroke patients and is known to be common in patients with thalamic injuries [6]. Third, the NCS and EMG findings were compatible with left L5 radiculopathy, and the LS spine MRI revealed a left foraminal protrusion at the L4-5 level. Therefore, we did not immediately suspect that the patient's lipoma was irritating the sciatic nerve.

The presence of the sign of the buttock led us to focus on the extracapsular hip. This test can be performed quickly and easily in the clinic [7]. Although the sensitivity of this test is low, it is useful in physical examination, because it may exclude serious pathologies, such as septic arthritis, tumors, and osteomyelitis [2].

It is common for stroke patients to have pain, including musculoskeletal pain and CPSP. Kong et al. [8] reported that 42% of stroke patients experience pain for more than 6 weeks. Among them, 71% report musculoskeletal pain, and 29% have CPSP. The shoulder is the most common originating site of pain in patients with musculoskeletal pain, followed by the knee and hip. CPSP is caused by lesions of the somatosensory pathways of the brain. Its pathophysiology is not well understood, but several theories about it have been offered, including central disinhibition, alterations in spinothalamic tract function, thalamic changes, and central sensitization [3]. Clinically, CPSP is known to have symptoms similar to those of peripheral neuropathic pain. Therefore, physicians may overlook the underlying musculoskeletal sources of pain and proceed to order unnecessary tests. It is important to precisely understand the characteristics of pain and thoroughly identify causes of pain by means of clinical investigation.

We describe the first case of a symptomatic intermuscular lipoma compressing the sciatic nerve in a stroke patient with suspicious CPSP. It was initially detected by means of a valuable screening test, sign of the buttock. There are various factors that obscure accurate diagnosis in stroke patients. Clinicians should realize that physical examination is crucial to the diagnosis of rare cases such as this one.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.