Effect of Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effect of radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT) on hemiplegic shoulder pain (HSP) syndrome.

Methods

In this monocentric, randomized, patient-assessor blinded, placebo-controlled trial, patients with HSP were randomly divided into the rESWT (n=17) and control (n=17) groups. Treatment was administered four times a week for 2 weeks. The visual analogue scale (VAS) score and Constant-Murley score (CS) were assessed before and after treatment, and at 2 and 4 weeks. The Modified Ashworth Scale and Fugl-Meyer Assessment scores and range of motion of the shoulder were also assessed.

Results

VAS scores improved post-intervention and at the 2-week and 4-week follow-up in the intervention group (p<0.05). Respective differences in VAS scores between baseline and post-intervention in the intervention and control groups were –1.69±1.90 and –0.45±0.79, respectively (p<0.05), between baseline and 2-week follow-up in the intervention and control groups were –1.60±1.74 and –0.34±0.70, respectively (p<0.05), and between baseline and 4-week follow-up in the intervention and control groups were –1.61±1.73 and –0.33±0.71, respectively (p<0.05). Baseline CS improved from 19.12±11.02 to 20.88±10.37 post-intervention and to 20.41±10.82 at the 2-week follow-up only in the intervention group (p<0.05).

Conclusion

rESWT consisting of eight sessions could be one of the effective and safe modalities for pain management in people with HSP. Further studies are needed to generalize and support these results in patients with HSP and a variety conditions, and to understand the mechanism of rESWT for treating HSP.

INTRODUCTION

Hemiplegic shoulder pain (HSP) is one of the most common problems after stroke with a prevalence of 34%–84%, and it can inhibit recovery and reduce quality of life [12]. One pathology alone cannot account for shoulder pain after stroke. In general, the causes of HSP are thought to be subluxation of the shoulder, rotator cuff problems, adhesive capsulitis, and complex regional pain syndrome. In a patient with HSP, more than two types of shoulder pathology exist [3]. Because HSP can have multiple causes and patients have a variety of medical conditions, it is necessary to consider targeted treatments and the patient's status.

Well-known treatments for HSP are oral medications including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), a subacromial-subdeltoid bursa steroid injection or fluoroscopically guided anterior approach intra-articular steroid injection, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and range of motion exercises. However, treatments that are currently being used for HSP cause several complications such as mechanical injury to joint structures during fluoroscopically guided anterior approach intra-articular injection or blind intra-articular injection, and there are limitations on the use of steroids in patients who have underlying diseases and unstable medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiac problems, etc.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been suggested as a non-invasive and alternative treatment for shoulder pain, and the effects of ESWT on various musculoskeletal disorders have been reported [456]. ESWT is a sequence of single sonic pulses, which have a high peak pressure (100 MPa), fast pressure rise (<10 ns), and short duration (10 µs). During ESWT, shock waves are transmitted by an appropriate generator to a specific target area, with an energy flux density ranging from 0.003–0.890 mJ/mm2.

Compared to conventional focused ESWT, radial extracorporeal shock-wave therapy (rESWT) does not focus shock waves on a target zone. Because the waves of rESWT disperse eccentrically from the applicator tip without concentrating the shock wave field on the targeted tissue, ultrasound or fluoroscopy is not required. The therapeutic effect of rESWT occurs 0–3.5 cm deep within the skin's surface [78]. It has shown promising results in patients with musculoskeletal problems [9] and in those with various causes of HSP, including spasticity, rotator cuff problems, adhesive capsulitis, and complex regional pain syndrome [10111213141516].

Several studies on the effect of rESWT (or ESWT) in post-stroke patients have focused on the spasticity of muscles, and although research on shoulder pain after stroke has been conducted, to the best of our knowledge, none of the studies had a control group or assessed shoulder pain as a primary outcome [10]. Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate the beneficial effects of rESWT on HSP after stroke. We hypothesized that eight sessions of rESWT on the greater and lesser tuberosities as the insertion sites of subscapularis and supraspinatus would be safe and effective in reducing HSP symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

In our monocentric, randomized, patient-assessor blinded, placebo-controlled trial, we recruited patients who were hospitalized from March 2015 to July 2015. The study was approved by the appropriate ethical committees.

Patients who (1) understood the study process and signed the informed consent form, (2) had a brain lesion confirmed by brain imaging, (3) had the first stroke more than 3 months ago, (4) were hemiplegic due to stroke, and (5) had shoulder pain and limited range of motion (ROM) or loss of motion in the proximal arm on the hemiplegic side were included.

Patients who (1) could not express their own pain intensity, (2) had a history of trauma to the shoulder on the affected side or a history of surgery on the shoulder on the affected side, (3) had a history of prior use of oral NSAIDs 3 days before this study, (4) had a history of shoulder pain before the stroke, (5) took warfarin medication with an international normalized ratio above 4.0, (6) had received a previous shoulder intra-articular injection or other interventions on the affected shoulder within 1 month before rESWT, (7) had received a cardiac pacemaker, (8) had osteoporosis, (9) refused the procedure before or during the study, and (10) had psychological problems were excluded.

A researcher who was not involved in processing or analyzing the data used a computerized randomization program, and patients were randomly assigned to the rESWT group or the control group.

Interventions

Each patient sat in a wheelchair or firm chair with the affected side of the shoulder kept open. HSP has various causes, including rotator cuff tendinopathies, adhesive capsulitis, spasticity, complex regional pain syndrome; therefore, to determine the effect of rESWT on the causes of HSP, we referred to previous studies in which rESWT was used to treat shoulder problems [10111213].

In the studies on the effect of ESWT on shoulder pain, Galasso et al. [11] performed stimulation around the supraspinatus tendon, Kim et al. [10] used the subscapularis muscle belly as the target site, Seo et al. [12] performed stimulation around the rotator cuff tendons in their study of rotator cuff tendinopathy, and Chen et al. [13] used three target sites around the shoulder in their study of adhesive capsulitis. By referencing these previous studies, we arbitrarily chose the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humeral head as the stimulation sites to stimulate rotator cuff tendons and the shoulder capsule. These stimulation sites were the subscapularis and supraspinatus insertion sites, and the stimulations were guided by ultrasonography.

The ultrasonography-guided interventions were performed by a single rehabilitation physician who did not assess the outcome measures. The shoulder was externally rotated, and the elbow was flexed at 90° to stimulate the subscapularis insertion site. To stimulate the supraspinatus insertion site, the shoulder was internally rotated, and the elbow was slightly extended.

The Masterpuls MP200 (Storz Medical AG, Tagerwilen, Switzerland) was used to perform rESWT (Fig. 1A).

(A) The stimulator. (B) The stimulator head and transmitter, and the stimulator head without the transmitter. In the radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy group, stimulation was delivered by the stimulator head with the transmitter; however, in the control group, patients received the same frequency but that of air pressure via the stimulator head without the transmitter.

In a previous study by Kim et al. [10], treatment was performed 5 times for 2 weeks. In our study, treatment was administered four times a week for 2 weeks (a total of eight sessions), which was more intensive than the treatment in the study by Kim et al. [10]. Patients received 3,000 pulses, 1,500 pulses per site at a frequency of 12 Hz per session with the submaximal pressure between 0.39 and 1.95 mJ/mm2 (1.0 and 5.0 bar), depending on the level which the patient could tolerate without local anesthetics.

In the control group, the same protocol was used. Sham stimulation was performed as in previous studies with a control group. In these studies, sham treatments were performed by using the same sound from a compact disc player without stimulation [11] or minimal stimulation [17] to create a similar situation, except without shock wave stimulation. In our study, stimulation was not delivered as the transmitter head was removed; hence, the patients received the same frequency of air pressure and sound (Fig. 1B).

Outcome measures

Information on the general characteristics was collected from patients' medical records. Abduction muscle strength of the shoulder on the affected side was assessed using the manual muscle test, along with the Medical Research Council scale and Brunnstrom stage, and outcome measures were assessed by a single rehabilitation physician who was blinded to randomization. Outcome measures were evaluated before (baseline) and after 1 day of the 2-week intervention (post-intervention), and follow-up evaluations were performed at 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the intervention (Fig. 2).

Outline of the treatment session and follow-up data collection. All patients were evaluated at baseline, 1 day after stimulation (real or sham), and at 2 weeks and 4 weeks after radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT).

As primary outcome measures, the visual analogue scale (VAS) score of the affected shoulder and the Constant-Murley score (CS) were used. Secondary outcome measures were the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) score, ROM of the glenohumeral joint of the affected side (flexion, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation), and Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Assessment (FMA-UE) score.

The subjective intensity of shoulder pain was measured using a 10-cm VAS. VAS is the most commonly used scale for the quantification of pain. There is evidence showing that it has superior metrical characteristics than discrete scales; thus a wider range of statistical methods can be applied to the measurements [18].

The CS is a functional evaluation method for the shoulder. The CS is composed of four domains: pain intensity, limitation of activities of daily living, mobility of the shoulder joint (ROMs for flexion, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation), and muscle power of the shoulder. The CS is based on a 100-point scale, composed of subjective and objective parameters. Subjective measurements yield 35 points. Objective measurements are awarded a maximum of 65 points, with 40 points for full ROM and 25 points for normal muscle strength [19].

The MAS score is the most commonly used to manually assess spasticity. For the convenience of performing statistical analysis, a MAS grade 1+ was matched to 2 points; and grades 2, 3, and 4 were matched to 3, 4, and 5 points, respectively [20].

ROM was measured passively with a goniometer for forward flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation of the shoulder. The measurement was taken with the patient in a sitting position.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test to determine comparisons between the rESWT and control groups at baseline.

To analyze the effects of the intervention within groups, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. Differences between post-intervention and baseline, between 2-week follow-up and baseline, and between 4-week follow-up and baseline were calculated in both groups.

To determine the intra-individual difference between the rESWT and control groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The values reported post-intervention minus those at baseline in the rESWT and control groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Similarly, the 2-week follow-up data minus the baseline data, and the 4-week follow-up data minus the baseline data between the rESWT and control groups were analyzed.

To investigate the predictive value of the effect of rESWT, multiple linear regression analyses using the backward elimination technique were applied to the data from the rESWT group to determine the correlation between baseline variables and the degree of pain reduction after 2 weeks of rESWT intervention.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software ver. 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

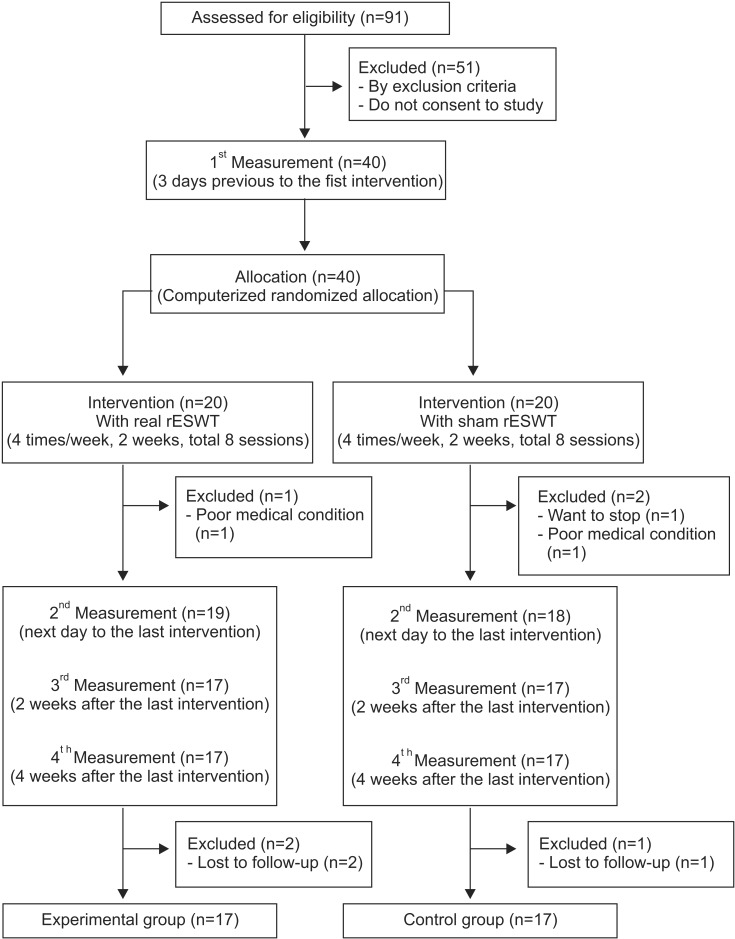

Of the 91 stroke patients screened, 40 were enrolled in the study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The flow chart of the study patients and a description of the missing data are presented in Fig. 3.

General characteristics

Thirty-four patients included 17 men and 17 women. Of the 17 subjects in the rESWT group, 7 were men and 10 were women, whereas the control group was composed of 10 men and 7 women. The average age was 65.88±8.27 years and 66.11±15.79 years in the rESWT and control groups, respectively. After performing the chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test to examine the preliminary homogeneity of baseline variables between the two groups, both groups were found to be homogeneous as there was no significant difference (p>0.05) (Table 1).

Primary outcome measures

Pain intensity (VAS)

The VAS score significantly improved post-intervention and at the 2-week and 4-week follow-up compared to baseline in the intervention group. The VAS scores at baseline before treatment, post-intervention, 2-week follow-up, and 4-week follow-up were 5.01±1.21, 3.32±1.50, 3.41±1.54, and 3.40±1.52, respectively (p<0.05). In the control group, the VAS scores significantly improved post-intervention from 5.05±1.34 to 4.60±1.20 (p<0.05).

Respective differences in the VAS score between baseline and post-intervention in the intervention and control groups were –1.69±1.90 and –0.45±0.79 (p=0.038), between baseline and 2-week follow-up in the intervention and control groups were –1.60±1.74 and –0.34±0.70 (p=0.009), and between baseline and 4-week follow-up in the intervention and control groups were –1.61±1.73 and –0.33±0.71 (p=0.016), which were statistically significant (Table 2).

Constant-Murley score

The CS significantly improved from 19.12±11.02 at baseline to 20.88±10.37 post-intervention and to 20.41±10.82 at the 2-week follow-up only in the intervention group (p<0.05). The CS score at the 4-week follow-up was 20.05±11.34 (p=0.064), and when compared to the baseline value, it was not statistically significant.

Differences in the CS between baseline and post-intervention, 2-week follow-up, and 4-week follow-up in the intervention and control groups were slightly increased without statistical significance (Table 2).

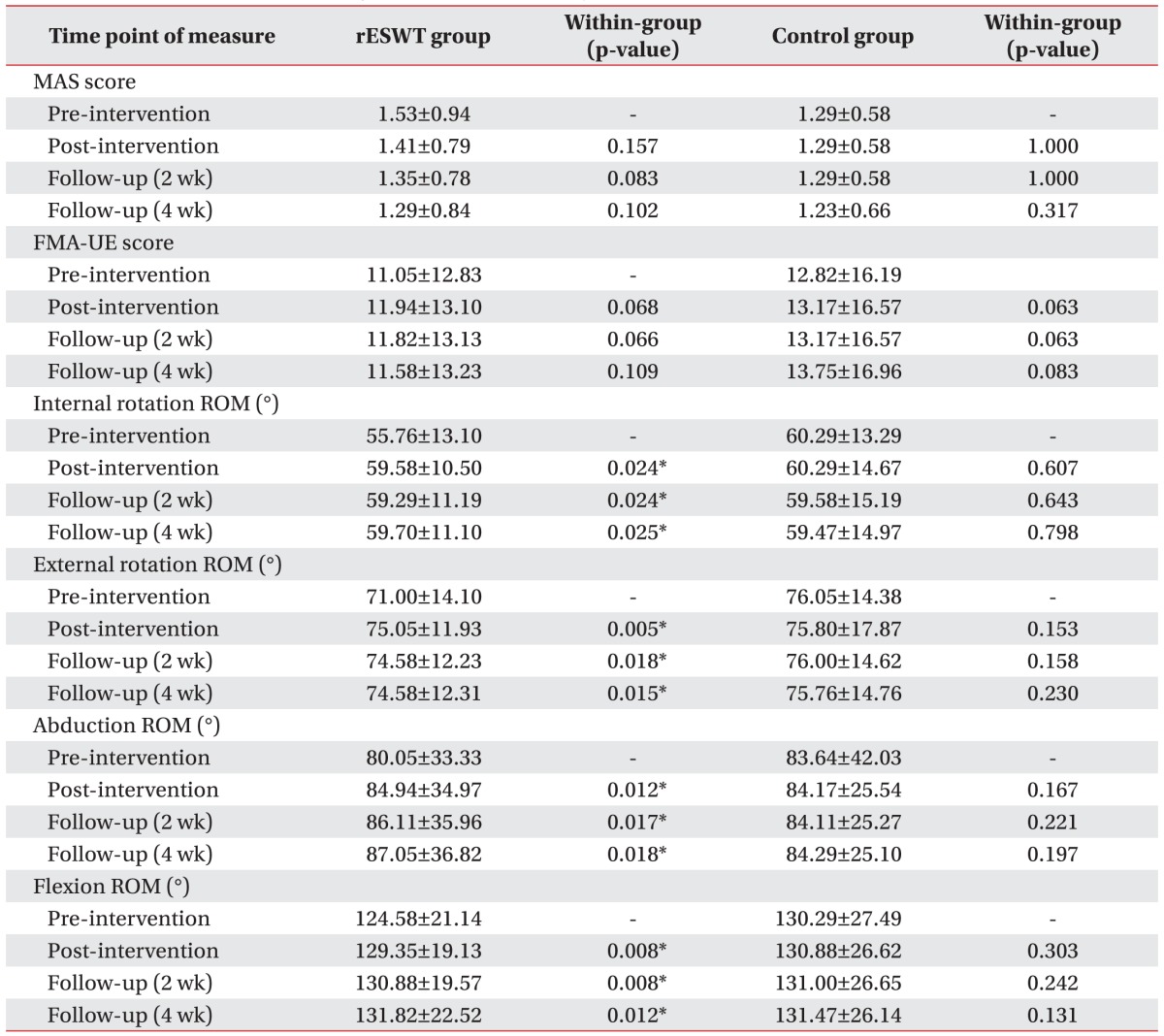

Secondary outcome measures

ROMs of the shoulder joint, including internal rotation, external rotation, abduction, and flexion, were significantly improved post-intervention, and at the 2-week and 4-week follow-up compared to those at baseline only in the intervention group (Table 3).

The MAS and FMA-UE scores in the rESWT group showed minimal improvement post-intervention, and at the 2-week and 4-week follow-up after the intervention compared to those at baseline, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.157, 0.083, and 0.102, respectively; p=0.068, 0.066, and 0.109, respectively) (Table 3).

Predictive value for the effect of rESWT

Among the baseline variables (age; pain duration; baseline VAS score, CS, MAS score, and FMA-UE score; and ROMs of the shoulder), only the baseline VAS score was correlated with the degree of pain reduction by rESWT with R2=37.4%, β=–0.962, and p=0.009.

Adverse events

After the eight sessions of rESWT, four adverse events were noted after the final intervention. Three patients had petechiae at the treatment site, which resolved spontaneously, and a small bulla was noted in 1 patient, which completely healed after a few days with a simple dressing.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled study that focused on the effects of rESWT on pain and function in people with HSP. The results of the study demonstrated that eight sessions of rESWT on the subscapularis and supraspinatus insertion sites of a hemiplegic shoulder reduced the pain and its effects lasted for at least 4 weeks.

Our results on the effectiveness of rESWT in HSP are similar to those of a previous study by Kim et al. [10], in which the pain was reduced and the effect was maintained for 4 weeks. Although the mechanisms of the pain improvement effect with rESWT (or ESWT) are unclear, it has been proposed that rESWT generates oscillations in tissue that leads to improved microcirculation and metabolic activities [21]. The immediate pain reduction effect after rESWT (or ESWT) can be explained by the result of a hyperstimulation analgesic effect [22]. Other mechanisms underlying the various causes of HSP, including rotator cuff problems, adhesive capsulitis, and complex regional pain syndrome, were suggested to lead to the anti-fibrotic effect [23], anti-inflammatory effects [11], and modulation of pain [14].

In the present study, the control group also showed pain improvement post-intervention, but the degree of pain improvement was negligible compared with that in the rESWT group, in which the difference was statistically significant. The placebo effects of ESWT have been suggested in various musculoskeletal conditions, including shoulder pain and soft-tissue lesions [242526]. The placebo and time effect can influence the results of pain improvement in a placebo group [27], but in the present study, the placebo effect seemed minimal.

In our study, the amount of pain reduction after intervention was 1.69 (from 5.01 to 3.32) and 0.45 (from 5.05 to 4.60) in the real rESWT group and the control group, respectively. The amount of pain reduction in the real rESWT group was considered to be too small to ensure patient satisfaction and the difference between the results of the two groups did not seem to be large enough. However, the clinical meaning that we derived from these results was that pain reduction to a VAS score of less than 4 was seen only in the real rESWT group.

In terms of functional improvement in the shoulder after rESWT (or ESWT), there have been conflicting results [1728]. Our study focused on patients with HSP, and improvement in the CS occurred and its effect lasted for only 2 weeks after the intervention with statistical significance in the rESWT group; however, the effect did not reach statistical significance in the between group analyses. Improvement of the CS score was not considered to have a clinical significance. The shoulder muscle strength in the enrolled patients with HSP was too weak to show a significant functional improvement. Further future studies are needed to determine functional improvement after rESWT in patients with HSP who have a minimal loss of shoulder muscle strength.

The results of the current study correspond with those of previous studies that demonstrated a positive effect on the ROM of the shoulder [2930]. HSP is associated with limited ROM of the shoulder [3132]. This is thought to be due to a combination of synovial inflammation and capsular fibrosis [333435], and they can aggravate the conditions of decreased active shoulder movement because of paralysis, synergistic pattern movements, and spasticity. The histologic features of adhesive capsulitis are capsular thickening and contracture of the ligaments around the shoulder, which is accompanied by an increased level of several inflammatory cytokines [333435]. The anti-inflammatory effects and anti-fibrotic effects of ESWT have been proposed as the mechanism of therapeutic effects of rESWT in several studies [233637], and this seems to be a possible explanation for the positive effect on ROM in the current study.

In our study, spasticity assessed by the MAS score improved but the result did not reach statistical significance. Unlike our study, Vidal et al. [29] showed a significant decrease in spasticity measured by the Ashworth scale in spastic cerebral palsy patients after rESWT. In studies on stroke patients, spasticity was also improved [15163038]. The mechanisms of ESWT on spasticity after stroke are still unknown. Variable mechanisms have been proposed, including induction of nitric oxide synthesis, decrease in spinal excitability, and induction of mechanical vibrations [39]. There are several reasons for the absence of change in the MAS score in the present study. In many studies that showed decreased spasticity after ESWT, the stimulation sites included the muscle belly or musculotendinous junction, but in our study, the muscle insertion sites were stimulated. The initial lower MAS score and flaccidity of the hemiplegic shoulders in our study may have occurred due to another reason.

Among various predictive values, higher pain scores were associated with better treatment outcomes following rESWT treatment. This is an interesting result, as it conflicts with the result of a previous study [40].

In our study, about half of the patients in the rESWT group had a VAS score of less than 5. The small amount of pain reduction in the real rESWT might be considered to be due to the proportion of patients with initial lower VAS scores in the rESWT group. In order to verify the actual pain relief effect, further study assessing the patient's satisfaction after treatment is needed.

The limitations of our study include the small number of subjects; in this situation, we used nonparametric methods so that statistical power was reduced. Therefore, the study sample was too small to generalize the results of our study.

Another limitation was the relatively short follow-up duration. Since our follow-up period was 4 weeks after the last rESWT, long-term follow-up studies are needed to precisely assess the duration of the effect of rESWT. Comparative studies on HSP treatments, such as steroid intra-articular injections, oral medications, and TENS, and on the treatment protocol of rESWT are needed in the future.

The current study demonstrated that eight sessions of rESWT at the subscapularis and supraspinatus insertion sites improved the VAS score in patients with HSP. Therefore, rESWT could be one of the effective and safe modalities for pain management in people with HSP. Further studies with various treatment protocols are needed to generalize and support these results in patients with HSP and a variety conditions, and to understand the mechanism of rESWT for treating HSP.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.