Relationship Between Cognitive Perceptual Abilities and Accident and Penalty Histories Among Elderly Korean Drivers

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between cognitive perceptual abilities of elderly drivers based on the Cognitive Perceptual Assessment for Driving (CPAD) test and their accident and penalty histories.

Methods

A total of 168 elderly drivers (aged ≥65 years) participated in the study. Participant data included CPAD scores and incidents of traffic accidents and penalties, attained from the Korea Road Traffic Authority and Korea National Police Agency, respectively.

Results

Drivers' mean age was 70.25±4.1 years and the mean CPAD score was 52.75±4.72. Elderly drivers' age was negatively related to the CPAD score (p<0.001). The accident history group had marginally lower CPAD scores, as compared to the non-accident group (p=0.051). However, incidence rates for traffic fines did not differ significantly between the two groups. Additionally, the group that passed the CPAD test had experienced fewer traffic accidents (3.6%), as compared to the group that failed (10.6%). The older age group (12.0%) had also experienced more traffic accidents, as compared to the younger group (2.4%).

Conclusion

Overall, elderly drivers who experienced driving accidents had lower CPAD scores than those who did not, without statistical significance. Thus, driving-related cognitive abilities of elderly drivers with insufficient cognitive ability need to be further evaluated to prevent traffic accidents.

INTRODUCTION

The total number of accidents involving Korean drivers has been decreasing in the last decade; however, the number of accidents involving drivers ≥65 years of age has been increasing. In 2014, the Korea Road Traffic Authority reported a decrease in the total number of accidents by an average of 1.6% per year, resulting in a decrease from 260,579 (13.1 people per 1,000) in 2001 to 215,354 (7.5 per 1,000) in 2013 [1]. On the other hand, the number of accidents by elderly drivers ≥65 years of age has increased by an average of 13.7% per year, with 3,759 (10.4 per 1,000) in 2001 to 17,590 (9.4 per 1,000) in 2013. Thus, despite the decreasing trend in the total number of accidents, the number of accidents by elderly drivers over 65 continues to increase. Consequently, there is a need to implement safety measures for elderly drivers.

Driving is a complex action that requires skills and proper functioning of vision, cognition, and mobility; thus, age-related decreases in cognitive, executive, and physical functions can lead to unsafe driving [2]. Cognition is particularly important for making appropriate judgments and decisions while driving. Therefore, attention, reaction time, memory, executive function, and mental status, as well as visual and physical functions are related to driving outcome measures among the elderly [3]. Thus, assessment of cognitive abilities of the elderly is required for safe driving. In many countries, evaluation tools such as the useful field of view (UFOV) [45], Cognitive Behavioral Driver's Inventory [6], Sensory-Motor Cognitive Test [7], and Driving Awareness Questionnaire [8] are used to assess drivers' cognitive abilities.

In Korea, the Cognitive Perceptual Assessment for Driving (CPAD) is currently used to assess drivers' cognitive functioning. The CPAD was developed by the National Rehabilitation Center of Korea to assess the driving abilities of patients with brain injury. It consists of a number of tests that evaluate depth perception, sustained attention, divided attention, digit span, and field dependency, as well as the Stroop test and the Trail Making Test-A/B (TMT-A/B). The CPAD assesses a total of 8 areas with 10 response measures including 6 correct responses and 4 reaction times [9]. The positive predictability of CPAD is 90.7%, and the internal consistency by Cronbach's alpha is 0.85 [10].

Based on total CPAD scores, drivers are divided into three groups i.e., pass group (score over 53), borderline group (score between 43–52), and failure group (score below 42). CPAD is a validated tool for evaluating driving abilities of patients with brain injury [11]. Studies have reported that CPAD scores are highly related to elderly people's cognitive perceptual abilities when driving. Park et al. [121314] reported that low CPAD scores are related to unsafe steering, vehicle positioning, lane changes, and car crashes; and unsafe driving and crashes during driving simulation have greater impact on elderly than younger drivers. Furthermore, in comparison to young drivers, elderly drivers experience declines in visual function, cognitive perceptual function, motor function, and driving performance. Consequently, low CPAD scores among elderly drivers are related to decreased driving performance. However, the relationship between elderly drivers' cognitive perceptual function and the actual occurrence of accidents remains unclear.

Although the number of motor vehicle accidents by Korean elderly drivers is increasing, the law does not require tests of cognitive abilities in elderly drivers. The Korea Road Traffic Authority uses the CPAD, developed by the National Rehabilitation Center of Korea, as a method of elderly driver safety education, and offers a 5% insurance discount to elderly drivers who pass the test. The goals of this educational program are to decrease the number of accidents and provide opportunities for elderly drivers to recognize changes in their physical function and ability to drive safely.

This study aimed to investigate differences in elderly drivers' driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities according to their accident histories. The assessment of the relationship between elderly drivers' cognitive perceptual abilities and accident histories was conducted based on their driving records provided by the Korea National Police Agency, and CPAD data provided by the Korea Road Traffic Authority.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

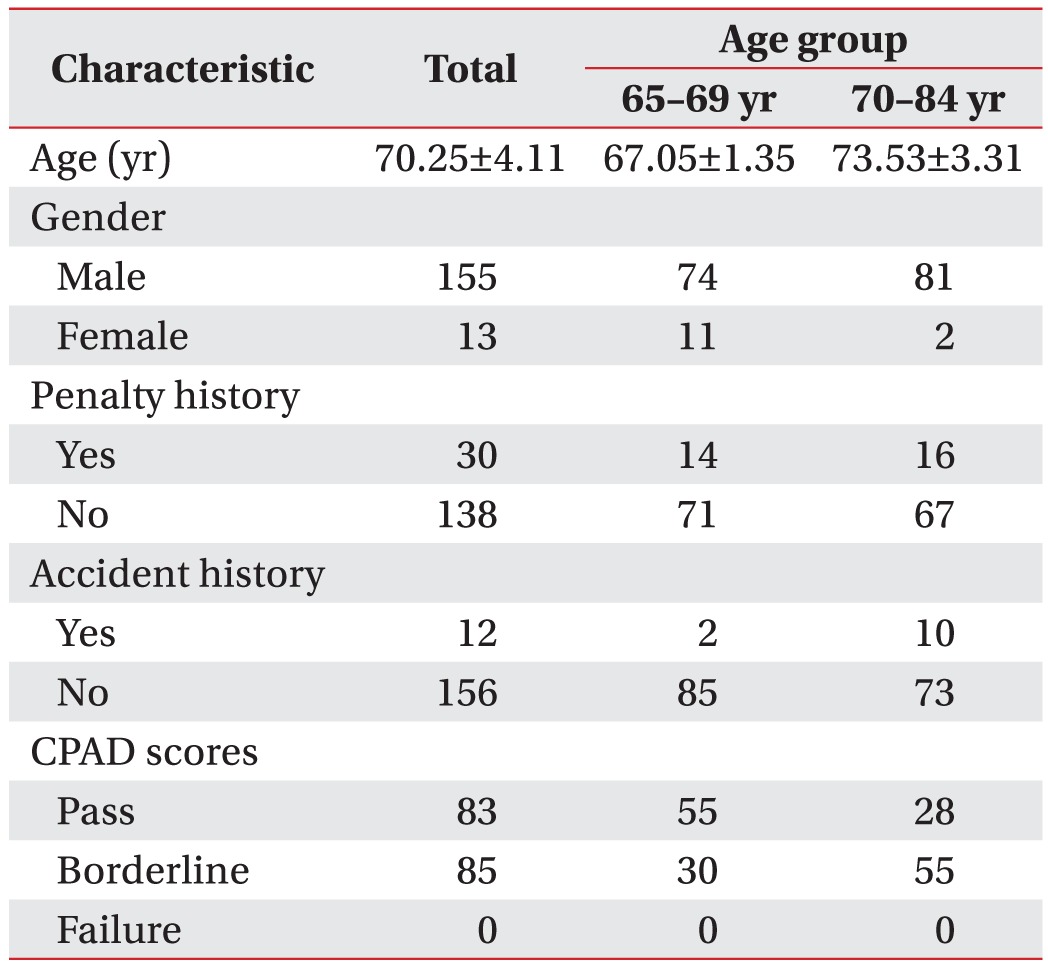

Elderly drivers included 168 elderly individuals >65 years (Table 1). All elderly drivers had a current driver's license and drove in daily. Elderly drivers voluntarily participated in the safety education program for the elderly provided by the Korea Road Traffic Authority and took the CPAD test. Additionally, they consented to access of their driving records from the Korea National Police Agency. Driving records included elderly drivers' accident and penalty histories between January 1, 2009 and June 30, 2014.

An accident was defined as actions such as impulse, collision due to violation of traffic signals, collision due to driving while drowsy, collision with a pedestrian, collision with a guardrail, and collision due to slippery road conditions. Accidents that involved a pedestrian included actions such as collisions with individuals crossing the road, walking on the roadway, walking on the sidewalk border, and walking on the sidewalk. Accidents involving another moving car included actions such as a head-on collision, right-angle collision, or rear-end collision. Finally, accidents that did not involve a pedestrian or moving car included actions such as a collision with other road structures, departure from the roadway, collision with stopped cars, and a car rollover. Additionally, penalties were defined as fines for traffic-related regulations such as violating the speed limit and traffic signals or instructions.

We acquired participants' CPAD scores from the Korea Road Traffic Authority and their accident and penalty histories from the Korea National Police Agency. Data provided by the Korea Road Traffic Authority included participants' CPAD scores, gender, and age. Data provided by the Korea National Police Agency included their accident and penalty histories.

Of the 168 participants, 85 were between 65 and 69 years of age, 58 were between 70 and 74, 17 were between 75 and 79, and 8 were between 80 and 84, respectively. We divided participants into two groups including participants between 65 and 69 years (n=85) and between 70 and 84 years (n=83), based on reports that older adults' accident rates sharply increase after the age 70 years [15].

Independent t-tests were conducted to compare between-group CPAD scores. We also conducted Mann-Whitney tests to assess differences in participants' driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities according to their accident and penalty histories.

Additionally, participants were divided into borderline and pass groups depending on CPAD scores. Accident histories were compared using cross tabulation analyses. SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses and the level of significance for statistical tests was set at a p-value of 0.05.

RESULTS

Elderly drivers' CPAD scores according to age

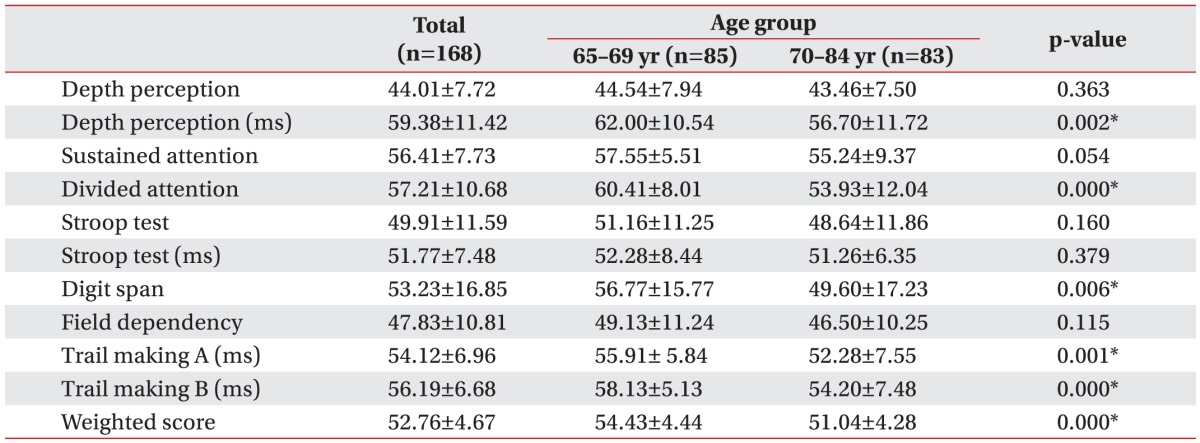

Elderly drivers between 65 and 69 years of age had a mean total CPAD score of 54.43; while elderly drivers between 70 and 84 years had a mean score of 51.04, with significant between-group difference (Table 2). With regard to individual CPAD test areas, the group with higher mean age was significantly slower in responding to the depth perception test and had significantly lower scores on the divided attention, digit span, TMT-A, and TMT-B tests (Table 2).

Elderly drivers' CPAD scores according to accident history

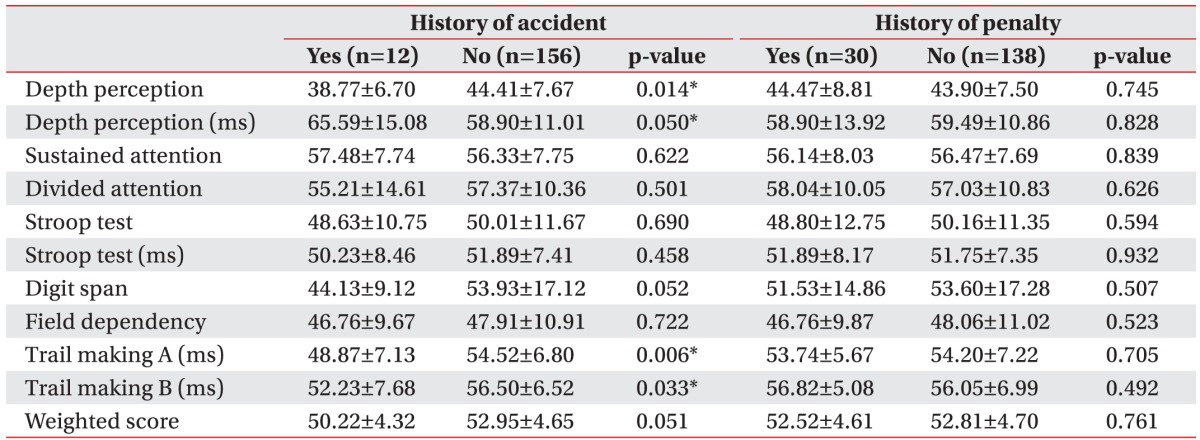

CPAD scores were higher in the non-accident group than in the accident history group (Table 3). Specifically, the accident history group exhibited significantly lower scores on the depth perception, TMT-A, and TMT-B tests than the non-accident history group; in addition, the accident history group had a lower total score, without significance (p=0.051) (Table 3). With regard to participants' penalty history, the 8 individual CPAD test scores showed no significant difference between penalty and non-penalty groups.

Cross tabulation analysis of elderly drivers' CPAD scores and age group according to accident history

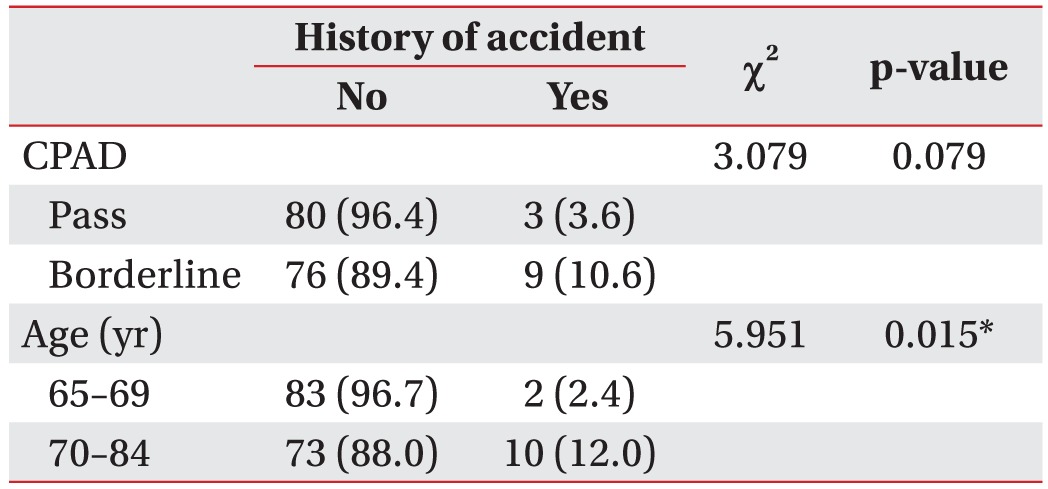

Based on CPAD scores, 83 elderly drivers passed, 85 were classified as borderline, and no elderly drivers failed. Cross tabulation analysis of the relationship between CPAD scores of the pass and borderline groups and their accident histories yielded a chi-square value of 3.079 (p=0.079), with no significant between-group differences. However, the accident rate was higher in the borderline than pass group (10.6% and 3.6%, respectively) (Table 4).

Cross tabulation analysis of elderly drivers' Cognitive Assessment Perception for Driving (CPAD) scores and age groups according to accident history

The cross tabulation analysis of the relationship between 65–69 age group and 70–84 age group and their accident histories yielded a chi-square value of 5.951 (p=0.015), with significant between-group differences. Specifically, the accident rate was higher in the older group than the younger group (12.0% and 2.4%, respectively) (Table 4).

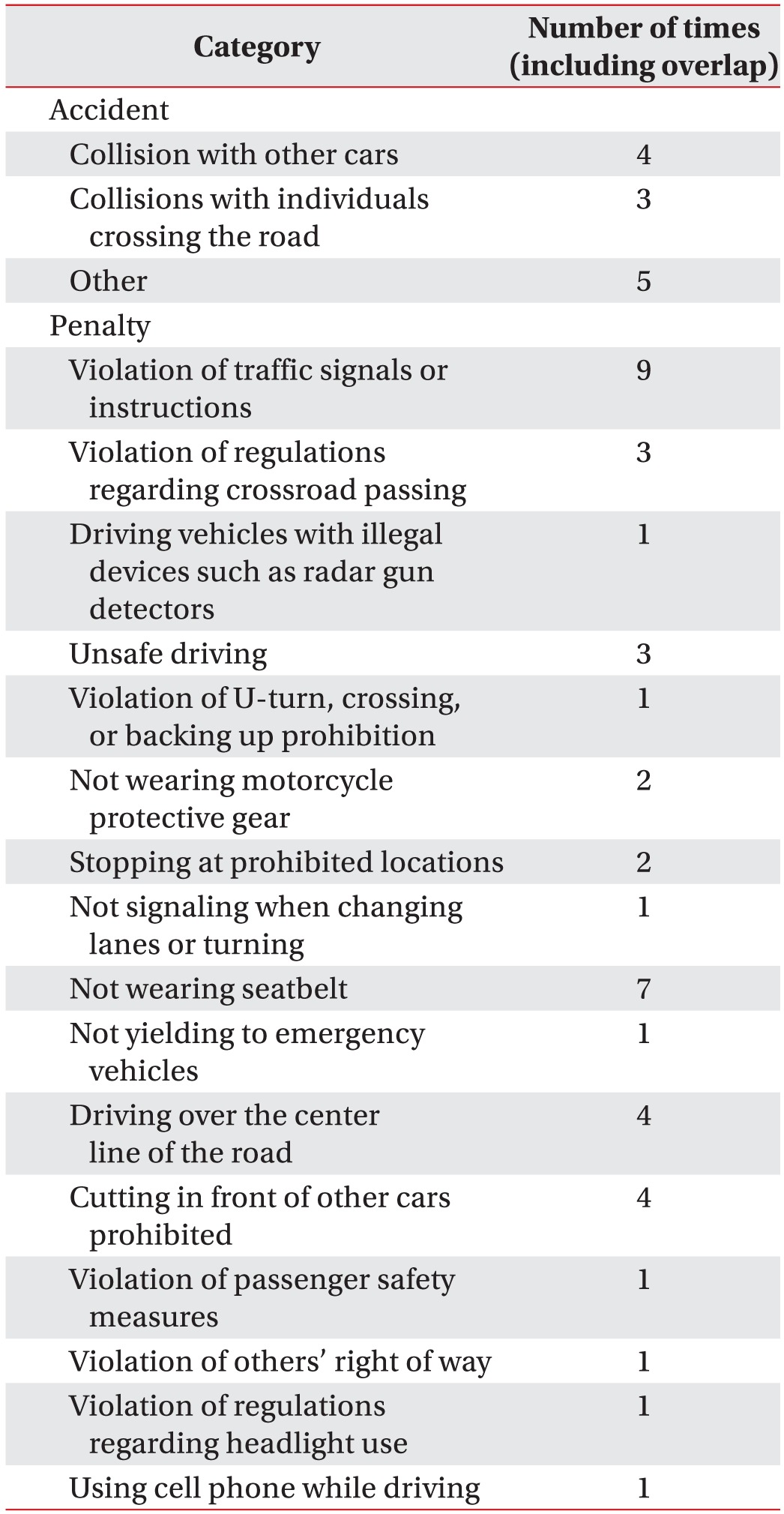

Elderly drivers' accident and penalty histories

According to elderly drivers' accident and penalty records, accidents primarily involved collisions with other cars, and penalties were mostly imposed for violating traffic signals or instructions and not wearing seat belts (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the relationship between elderly drivers' who took the CPAD test of driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities and their accident history. The accident history group had lower CPAD scores, as compared to the non-accident group, without significant between-group difference. The older age group had experienced more traffic accidents, as compared to the younger group. The older group also (ages 70–84 years) had significantly lower CPAD scores, as compared to the younger group (ages 65–69 years). Thus, older adults' accident rates increased significantly after the age of 70, and aging negatively affected the cognitive skills necessary for safe driving.

Depth perception tests that assess drivers' perceptions of distance and depth showed no significant between-group difference; however, the group with the higher mean age had a longer response time. The results of divided attention test that measures drivers' ability to divide attention and respond to various stimuli while driving indicated that attention levels were lower in the group with the higher mean age. The digit span test that measures drivers' short-term memory indicated that memory had declined in elderly drivers. Thus, the group with higher mean age responded significantly slower in the depth perception test and had significantly lower scores in the divided attention, digit span, TMT-A, and TMT-B tests. The CPAD is a test that measures drivers' coordination of visual and motor skills as well as their ability to perceive necessary information under complicated driving conditions. Five of 10 individual CPAD test areas showed significant differences between age groups; however, the group with a higher mean age had lower scores than the group with a lower mean age in all individual test areas. These differences could be attributed to the influence of aging on drivers' driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities. Specifically, as individuals age, they experience difficulties in safe driving not only due to a decline in physical abilities, but also due to a decline in cognitive perceptual abilities (e.g., judgment making on the road and attention) [16]. Similarly, a study reported that geriatric illnesses due to aging, rather than aging itself, impacts cognitive and physical modes of driving [17].

As the elderly experience a decline in depth perception, sustained attention, cognitive function, and physical abilities, self-evaluation of driving ability is required. The CPAD is a cognitive testing tool to determine decline in specific cognitive abilities and evaluate the elements of cognitive attention required for driving. Driving-related cognitive perceptual function does not aim to limit the mobility or freedom of the elderly, but instead, to educate and help them realize that these functions are necessary for personal safety. Such education would enhance elderly drivers' defensive driving skills by helping them recognize their individual weaknesses and prevent accidents through driving simulation and training.

Elderly drivers who experienced previous accidents generally showed lower CPAD scores than drivers who did not. In particular, the accident history group had significantly lower scores in depth perception, TMT-A, and TMT-B tests. The elderly generally have narrower fields of vision and weakened eyesight due to decline in visual function. Moreover, in relation to depth perception, as spatial vision contrast decreases, the concentration range of elderly drivers becomes limited, together with their ability to clearly see objects.

Results of many studies suggest a relationship between driving and the TMT-B test, which measures drivers' performance. The TMT-B is a simple and easy to administer test that evaluates the driving fitness of elderly drivers or drivers with cognitive impairments [181920]. Other studies have also reported a relationship between drivers' low TMT-B scores and accident rates [2122]. Thus, TMT-B is an appropriate component of CPAD tests of driving-related cognitive abilities. Overall, the TMT (TMT-A, TMT-B) is a simple and easy to administer neuropsychological test that measures cognitive abilities such as visual perception, pursuit eye movement, sustained attention, and task alternation [23]. The TMT-A and TMT-B are highly related to driving cognition and therefore appropriate as simple screening tests for driving cognition.

In the current study, lack of significant differences in total CPAD scores between age groups despite significant differences in certain CPAD test areas is possibly due to the small number of drivers (n=12) with an accident history. Cross tabulation analysis of elderly drivers' CPAD scores (pass/borderline) and accident histories indicated that 96.4% of the pass group (CPAD scores over 53) and 89.4% of the borderline group (CPAD scores between 43 and 52) had no accident history. However, the accident rate was higher in the borderline than pass group.

According to the 2013 study by the Korea Road Traffic Authority, 73.9% (13,007 cases) of elderly drivers' accidents were collisions with other cars. The main causes of accidents were unsafe driving (51.6%), and 12.9% were due to traffic signal violations [1]. Similarly, in the present study, most accidents involved collisions with other cars, and most violations involved traffic signals and instruction violations. However, CPAD scores showed no significant difference based on elderly drivers' penalty history (p=0.761), possibly because penalties influence drivers' behaviors and habits rather than driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities.

Over the last decade, elderly driver accidents have increased despite the decreasing trend in the total number of motor vehicle accidents in South Korea. As a result of an aging society, the percentage of people over 65 in the general population has increased resulting in an increase in the percentage of elderly drivers. Current lifestyles have also caused an increased need for elderly drivers to drive themselves rather than depend on others. Moreover, problems arise due to elderly drivers' physical and psychological functional decline and difficulty in maintaining awareness of changing traffic regulations [24].

As the number of accidents by elderly drivers is increasing, many countries conduct institutionalized tests to evaluate driving abilities. For instance, the United Kingdom requires aptitude and medical tests every 3 years for drivers over 70 years of age. Similarly, in France, aptitude and medical tests are required every 2 years for drivers between the age of 60 and 65 years and every year for drivers over 76. Japan requires the completion of a special educational program for drivers over 70, and those over 75 are also required to take cognitive tests. Additionally, Australia requires aptitude, medical, and driving tests for drivers over 80, and the United States requires visual and theory tests for drivers over 80 [25]. Although Korea requires aptitude tests for drivers over 65 every 5 years, tests of driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities are not conducted. Therefore, such tests should be included as part of the existing aptitude test, and related laws should be instated to protect the safety of the elderly and others.

The present study had several limitations. First, as the number of elderly drivers with accident histories was too small, the accident and non-accident group comparison was limited. Second, since elderly drivers voluntarily took the CPAD to attain an insurance discount, it is difficult to generalize the results to other elderly drivers. Third, the driving-related medical diagnoses or drug use status of elderly drivers enrolled in this study were not evaluated.

Follow-up studies are needed to analyze the cumulative data of the accident history group and investigate the relationship between accidents and driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities in elderly drivers who are required to take aptitude tests.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that driving-related cognitive perceptual abilities were lower among the older than younger elderly group, and these abilities were lower among those with accident histories than those without. However, elderly drivers' penalty histories for traffic law violations were unrelated to their cognitive perceptual abilities. Consequently, the driving-related cognitive abilities of elderly drivers with insufficient cognitive ability need to be evaluated to prevent traffic accidents.

In future, the law should mandate driving-related cognitive perceptual ability tests and education on safe driving among elderly drivers. Moreover, increased management of alternate means of transportation for the elderly is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant (14-C-04: A Study on the Effectiveness and Improvement of the CPAD) by Korea National Rehabilitation Research Institute.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.