Disaster Response and Management: The Integral Role of Rehabilitation

Article information

Abstract

With the increasing frequency of disasters and the significant upsurge of survivors with severe impairments and long-term disabling conditions, there is a greater focus on the importance of rehabilitation in disaster management. During disasters, rehabilitation services confront a greater load due to the influx of victims, management of persons with pre-existing disabilities and chronic conditions, and longer-term care continuum. Despite robust consensus amongst the international disaster response and management community for the rehabilitation-inclusive disaster management process, rehabilitation is still less prioritised. Evidence supports the early involvement of rehabilitation professionals in disaster response and management for minimising mortality and disability, and improving clinical outcomes and participation in disaster survivors. In the last two decades, there have been substantial developments in disaster response/management processes including the World Health Organization Emergency Medical Team (EMT) initiative, which provides a standardized structured plan to provide effective and coordinated care during disasters. However, rehabilitation-inclusive disaster management plans are yet to be developed and/or implemented in many disaster-prone countries. Strong leadership and effective action from national and international bodies are required to strengthen national rehabilitation capacity (services and skilled workforce) and empower international and local EMTs and health services for comprehensive disaster management in future calamities. This narrative review highlights the role of rehabilitation and current developments in disaster rehabilitation; challenges and key future perspectives in this area.

INTRODUCTION

Disaster is a “serious disruption of functioning of a community or a society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources” [1]. Disaster can be classified into:

• Natural (e.g., earthquakes, storms)

• Technological or man-made - events caused deliberately by humans (e.g., armed conflicts, terror attacks and other situations of violence) or by human negligence (e.g., industrial or transport accidents)

• Complex humanitarian emergencies - events from several different hazards or a complex combination of both natural and man-made disasters with different causes (e.g., food insecurity, epidemics/pandemics, displaced populations).

This review will focus on natural disasters which are defined as “situation or event caused by nature, which overwhelms local capacity, necessitating a request to a national or international level for external assistance; an unforeseen and often sudden event that causes great damage, destruction and human suffering” [2]. Natural disasters can be sub-classified into different categories based on their etiology (Table 1) [3].

All types of natural disasters are increasing globally. According to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), between 2000 and 2019, 7,348 natural disaster events were recorded worldwide, which has almost doubled since 1998–1999 [4]. This is mainly attributed to a rise in the number of climate-related disasters (floods, storms, heatwaves, etc.), accounting for over three fourth of the total natural calamities (6,681 climate-related disasters between 2000 and 2019) (Fig. 1) [4]. Floods are the most common type of disaster (accounting for 44% of total events), followed by storms (28%), earthquakes and volcanic activity (9%), extreme weather events (6%), droughts (5%), and wildfires (3%) [4].

Total natural disasters by type 1980–1999 vs. 2000–2019. Source: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) (https://cred.be/sites/default/files/CRED-Disaster-Report-Human-Cost2000-2019.pdf) [4].

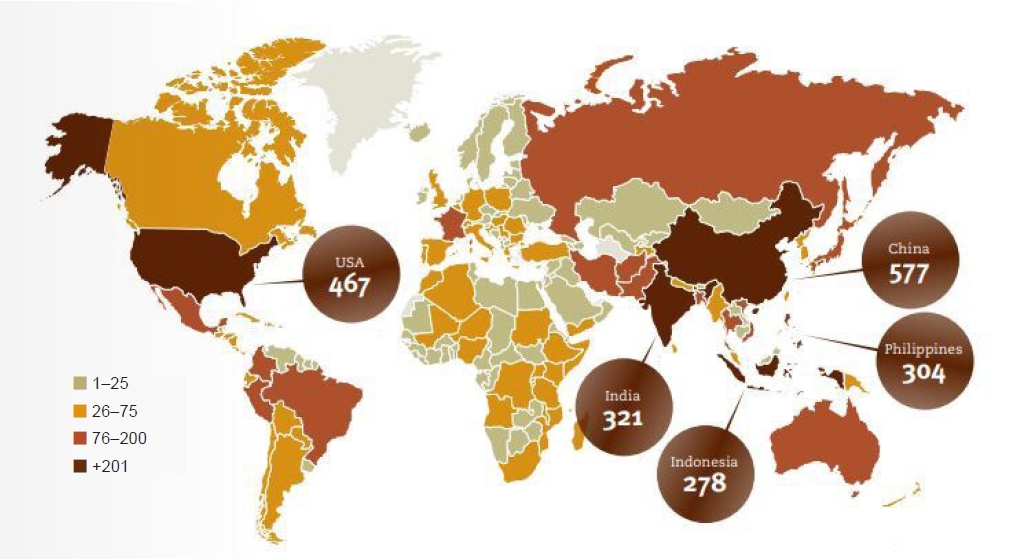

Natural disasters occur disproportionately and the majority occur in the low-resourced regions of the world. Asia-Pacific is the most disaster-prone region accounting for over 40% of the world's disasters in the past decade [4,5]. This is largely due to seismic fault lines and landscapes in the region that represent a high risk of natural hazards, such as river basins, flood plains [6]. Between 2000 and 2019, overall, eight of the top 10 countries by disaster events were in Asia, with China experiencing the most number of events (over 500 events) (Fig. 2) [4]. Further, Pacific Island Countries (PICs) are classified among the world’s top 30 most vulnerable nations to natural disasters, with approximately 41 tropical cyclones occurring each year [7].

Total number of disasters reported per country/territory (2000–2019). Source: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) (https://cred.be/sites/default/files/CRED-Disaster-Report-Human-Cost2000-2019.pdf) [4].

IMPACT OF NATURAL DISASTERS

Natural disasters result in significant loss of life and long-term disability from severe injuries. Depending on the nature and scale of disasters, the impacts on population, health, and infrastructure may differ, however, the outcomes to a large extent could be similar [8]. Between 2000 and 2019, the natural disaster claimed approximately 1.23 million lives (an average of 60,000 deaths per annum) and affected over 4 billion people (an average of 200 million per year) [4]. These have led to approximately USD 2.97 trillion in economic losses (almost doubled since 1980–1999) (Fig. 3). In recent years, there is a sustained rise in climate- and weather-related events (floods, storms, heatwaves, wildfires in particular) accounting for 41% of total deaths and over 3.9 billion affected in the period 2000–2019 [4]. Geophysical disasters (earthquakes including tsunamis) are associated with the highest impact on the human toll among all other types of disasters put together (accounting for 59% of all disaster-related deaths) [4]. In 2022 alone, 387 natural disasters worldwide killed over 30,700 people, affecting 185 million others and costing above USD 223.8 billion [9]. Fig. 3 shows the human impact of disasters comparing 1980–1999 with two decades ahead (2000–2019).

Impact of natural disaster between 1980–1999 vs. 2000–2019. Source: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) (https://cred.be/sites/default/files/CRED-Disaster-Report-Human-Cost2000-2019.pdf) [4].

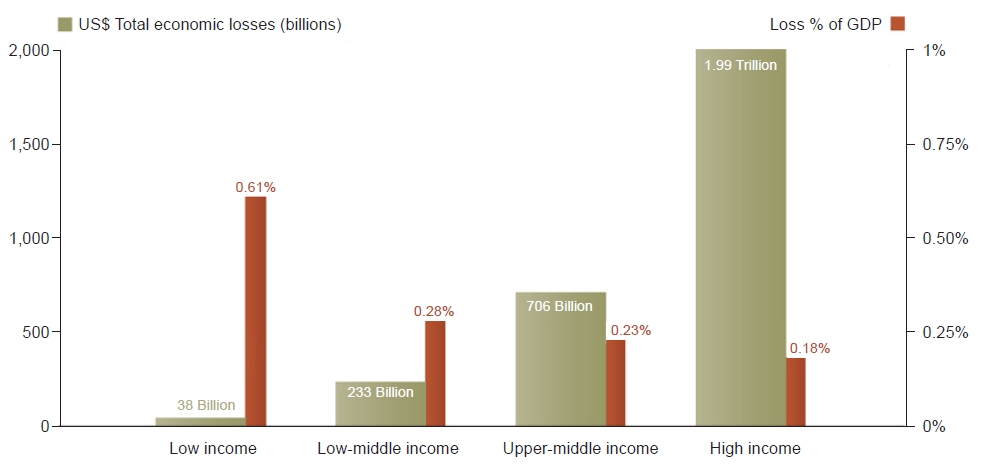

High-income countries experienced more disasters compared to low-income countries, and tend to have the most total economic losses. However, these countries have lower numbers of people affected and killed by disaster events, relatively due to better risk governance, infrastructure, surveillance systems, and reduced exposure to natural hazards. Low-income countries account for 23% of total disaster deaths and the highest average number of deaths per disaster event (284 per event) [4]. This is accompanied by a significant proportionate economic loss and long-term negative consequences on human development in these countries (3 times higher gross domestic product [GDP] losses compare to high-income countries) (Fig. 4) [4]. For example, PICs bear, combined disaster damages of more than USD 280 million on average every year, costing some countries up to 6.6% of their GDP [10]. The total value of economic damage and losses caused by the 2010 Haiti earthquake was estimated at USD 7.8 billion, surpassing the country’s GDP in 2009, which could delay the country’s economic development by 10 years [11]. Further, there was a substantial impact on health services with 30 out of 49 hospitals damaged or destroyed during this event [11].

Economic losses in absolute value (USD) compared to losses as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) by World Health Organization income group (2020). Source: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) (https://cred.be/sites/default/files/CRED-Disaster-Report-Human-Cost2000-2019.pdf) [4].

REHABILITATION NEEDS IN DISASTER SETTINGS

Despite saving lives immediately following disasters being an urgent priority, current, advances in disaster response and management, have resulted in a significant increase in survivors compared to mortality. This includes an upsurge in survivors with complex impairments and disability (temporary or permanent) from common injuries, such as musculoskeletal (bone fractures, limb amputations, crush injuries), spinal cord and/or traumatic brain injury, soft tissue and peripheral nerve injury, burns, etc. [12]. Overall injury patterns are poorly studied in natural disasters, and the type and severity of injuries vary according to various factors including the type of disasters and geological factors (disaster magnitude and intensity, epicentral distance, etc.), human/individual factors (demographics, physical location, and capabilities, behavior, etc.), and built environment (quality of building and infrastructure, population density, etc.) [13]. The most common type of injuries specifically in earthquakes, which contributes to the highest disaster-related mortality and morbidities, were reported to be orthopedic (87%), with lower extremities fractures being most prevalent (42%) [14,15]. Further, there is a substantial increase in the number of victims with exacerbation of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, etc.), psychological impairment (such as post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], depression, and other mental disorders) [16,17]. The common barriers reported to healthcare access during disasters included: limited and/or disrupted healthcare services, centralized healthcare infrastructure (mostly located in the metropolitan area), financial difficulties, access to transport, affordability of treatment and devices, displacement, and illiteracy [16]. Huang et al. [18] exploring the association of ischemic heart disease (IHD) with natural disasters in 193 countries reported an independent association between the IHD mortality rate (2.3 deaths per 100,000 population) and years of life lost (YLL, 31.1 years per 100,000), and occurrence of natural disasters (p<0.05 for both). Further, those with pre-existing disabilities are at risk of higher mortality rates and additional co-morbidities/impairments, especially those with mobility impairments [12]. These signify the important role of medical rehabilitation in the comprehensive disaster management plan.

The critical importance of rehabilitation during and after a natural disaster for the survivors is well-documented and the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that “rehabilitation is one of the core functions of trauma care systems in regular health care and, as such, Emergency Medical Team (EMT) should have specific plans for the provision of rehabilitation services to their patients post sudden onset disaster” [19,20]. The rehabilitation need and demand can have different patterns in emergencies, and may also differ over time [20]. However, based on clinical needs rehabilitation is required at all stages of the disaster management cycle: in the initial acute stage when there is the influx of trauma and non-trauma emergencies; in the post-acute period as complications arise and patients are prepared for discharge; and in the long-term in the community for those with complex, and permanent disabilities [20-22]. Demand for rehabilitation can peak in the first 3 weeks post-disaster and can increase over time, as triaging and discharge of patients (even those who are medically stable) can be problematic, due to the destruction or damage of their homes and livelihood. Further, demand for outpatient and community rehabilitation can spike post-disaster with added care requirements of persons with pre-existing disabilities and chronic conditions, creating additional service needs [20]. Thus, these indicate that rehabilitation services confront the greatest care burden during disasters. Fig. 5 indicates trends in the rehabilitation burden in disasters [21].

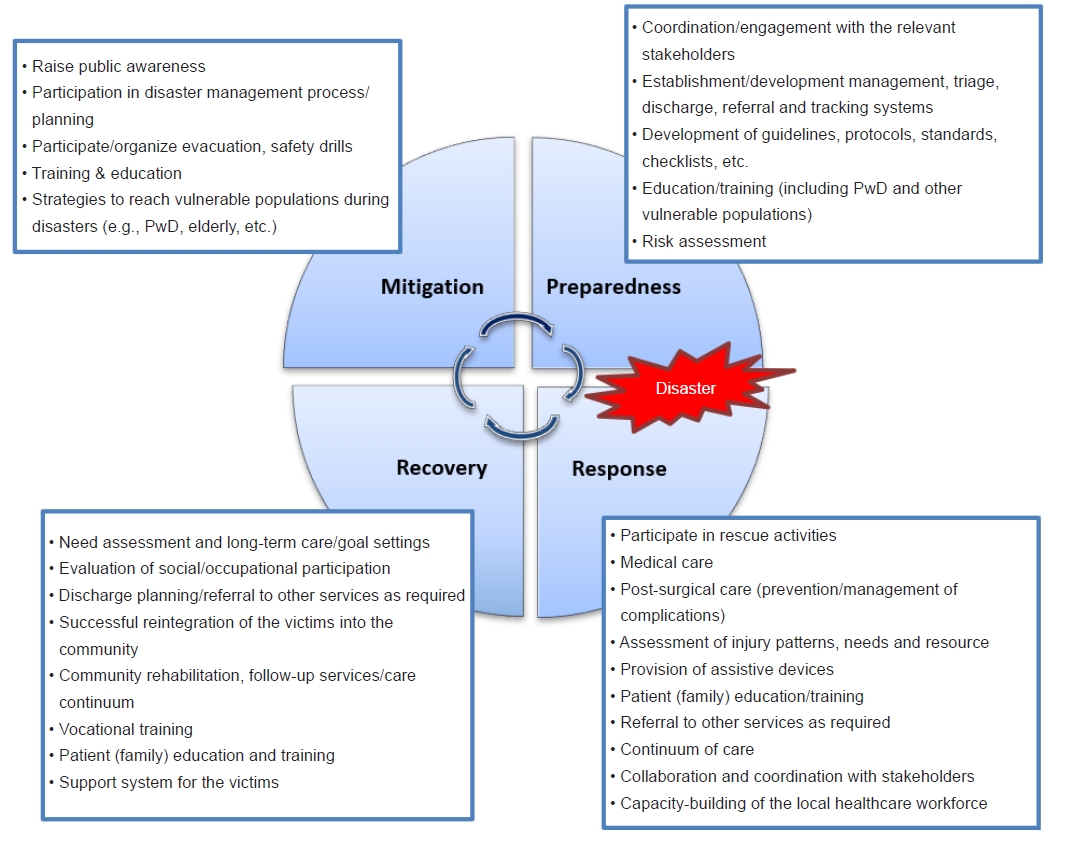

ROLE OF REHABILITATION PROFESSIONALS IN DISASTERS

The global health authorities emphasize that medical rehabilitation should be initiated acutely during the emergency disaster response and should be continued in the community over a longer-term [22-24]. The WHO World Report on Disability accentuates that “rehabilitation services are essential services to be provided by foreign aid for humanitarian crises” (p. 108) [25]. The “Sphere Project,” in its handbook “Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response,” further reinforces the importance of rehabilitation and states that surgery provided during a humanitarian crisis without any immediate rehabilitation can result in poorer patient outcomes [26]. This implies that rehabilitation service is required at all phases of the disaster management continuum, which comprises mitigation/prevention, preparation, response, and recovery phases [22,23,27]. It presents holistic patient-centered care for disaster victims delivered by an interdisciplinary team (medical, nurses, and allied health professionals) developed within available resources, to optimize function, improve activity and participation within contextual factors (personal and environmental) [28]. The role of rehabilitation professionals can be complex and requires a multi-faceted mix of skills and training in disaster continuum phases, including diagnostic, clinical management, educational and advocacy capabilities [23,29]. At times rehabilitation professionals will be required to stretch beyond the roles they are trained for to meet the complex needs of the overwhelming number of disaster victims. Some of the potential roles of rehabilitation personnel in the disaster management cycle are listed in Fig. 6.

Potential role of rehabilitation personnel in the disaster management cycle. PwD, persons with disabilities.

The number of international and local EMTs from governmental or non-governmental sources deployed to the disasters are steadily increasing. In many past disasters, deployment of EMTs was not solely based on the assessed needs of the affected state, and wide variations in their capacities, competencies and adherence to professional ethics can be noted [30]. For example, during the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the international humanitarian response was catastrophic, with the influx of a large number of unregistered EMTs who were unfamiliar with the international emergency response systems and standards, or coordination mechanisms [11]. The WHO EMT initiative now sets the core standards and guidance for EMTs within defined coordination mechanisms in this area [20]. Various guidelines and protocols have been developed including rehabilitation guidelines during disasters, launched in 2016. It provides minimum standards/requirements for all EMTs during deployments to disasters, regarding workforce, field hospital environment, rehabilitation equipment/consumables and information management (Appendix 1-3) [20]. It is recommended that the EMT needs to establish an action plan in consultation with the WHO EMT secretariat, local healthcare authorities, International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM), and appropriate experts [31]. The following important themes are required for consideration:

• Analysis: study the situation, risk assessments, requirements, etc.

• Objectives: set up key objectives, roles, and responsibilities

• Planning: team configurations, resources (finance, equipment), transportation, accommodation, logistics

• Execution: medical care, response, and management to achieve objectives

• Communication: briefing, reports, support activity, consultation

• Safety: patient and healthcare personal safety

• Transition: handover, care continuum of victims, local capacity building, foster partnership

• Research: evaluation, data collection, and dissemination, identify gaps/challenges, knowledge/information sharing

EVIDENCE OF REHABILITATION INTERVENTIONS IN DISASTER SETTINGS

Table 2 provides a summary of published studies evaluating various rehabilitation interventions in disaster settings. Early involvement in rehabilitation can result in better clinical outcomes, and improve participation and quality of life (QoL) of disaster victims [6,29,32,33]. Evidence from past disasters suggests that victims treated in centers with rehabilitation physician supervision had a reduced length of hospital stay, fewer complications and better clinical outcomes compared with patients without such provision [33,34].

Box 1. Summary of the desk review of the evidence of rehabilitation interventions in disaster settings

A rapid desktop review was conducted to update the evidence from our previous review published in 2015 [23] evaluating the effectiveness of medical rehabilitation intervention in natural disaster survivors. This comprehensive review included 10 studies (2 randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and 8 observational studies) that investigated a variety of medical rehabilitation interventions for natural disaster survivors, ranging from comprehensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation to community educational programs. This review highlighted the lack of high-quality evidence to support rehabilitation interventions used for disaster survivors. The gaps identified in the literature included the types of rehabilitation settings, modalities and duration of therapy, lack of effective care pathways, and long-term functional outcomes. A similar multipronged approach was used to search the literature (peer review, grey literature from the date of the last search date till May 2023) including search of the peer-review literature using medical and health science electronic databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library); manual search of bibliographies of relevant articles and journals; and search of grey literature using relevant Internet search engines and websites of prominent health care institutions, governmental and nongovernmental organizations associated with disaster management and rehabilitation.

The combined searches retrieved a total additional 260 published titles and abstracts. Twelve abstracts met preliminary inclusion criteria, and the full texts of these articles were assessed. In addition to the 10 articles included in our previous review [23], a further 8 articles (1 RCT, 2 controlled clinical trials, and 5 observational studies) which reported medical rehabilitation interventions after natural disasters were included (Table 2).

The published literature indicates that a wide variety of medical rehabilitation modalities are trialed in natural disaster survivors both in hospital and community settings. The evaluated interventions were heterogeneous (type, duration and mode of delivery) and specifically included, comprehensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation, physical modalities, psychological programs, community programs, and others. The majority included physical activity and psychosocial intervention as rehabilitation components. The study population group also differed in many facets.

The findings suggest that despite the lack of high-quality evidence for the effectiveness of many of the evaluated rehabilitation interventions, there is distinct evidence for the beneficial effect of medical rehabilitation for survivors of natural disasters in producing short and long-term gains for functional activities (activities of daily living, physical activity, etc.), impairments (e.g., psychological symptoms), and participation (QoL, social reintegration) [6,32,33]. Institution-based and community rehabilitation interventions provided by the multidisciplinary team to 2008 Sichuan earthquake victims in China were associated with significant improvement in functional outcomes, decrease symptoms and improved health-related QoL [32,35-43]. The rehabilitation interventions were the strongest predictor of increased and sustained functional gains and improved QoL in these patients [32]. Further, other studies demonstrated the beneficial effect of hospital-based and/or community-based rehabilitation programs in improving psychological issues such as anxiety, PTSD symptoms, distress and depression [17,36,39,41,44,45]. Zhang et al. [43] evaluated a long-term structured and coordinated rehabilitation services model that provided both comprehensive hospital and community-based rehabilitation, comprising nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), local health departments (H) and volunteers (V) for earthquake survivors in China. The findings suggest that the NHV comprehensive rehabilitation program benefitted the individual and society with significant improvement in long-term physical functioning [43]. Another study showed psychological rehabilitation intervention (structured in-community psychological care) significantly improved psychosocial symptoms (PTSD, depression, stress, etc.) in post-tsunami victims [44]. Group and social activities post-disaster were found to enhance victims' societal participation and improve psychosocial well-being [17,46-48]. Wu et al. [49] demonstrated that modern technological intervention (virtual reality videogames) adjunct to traditional occupational therapy interventions can have better improvement in function, scar management, and hand function in patients with severe hand burns. In another study, Fahmida et al. [50] showed that integrated community-based nutrition rehabilitation intervention can have benefits in reducing maternal stress, child morbidity and in improving the growth and development of children in post-disaster conditions. However, there was no evidence for the best type/mode/intensity (frequency, duration) of these interventions or the superiority of one intervention over another. There is a limited number of robust studies in this area, which reflects various ethical, methodological and logistical challenges in conducting research in disaster situations.

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS

Since the catastrophic disaster management process during the 2010 Haiti earthquake, there was a strong consensus amongst the international medical and humanitarian communities for a stringent approach to emergency response in future disasters in terms of governance, coordination, organisation, evaluation, professionalism and accountability. In the last decade, there have been many much-needed developments in disaster response and management (including rehabilitation) in international, regional and national collaboration and management capacities. The WHO’s EMT initiative is fundamental in this area to improve the timeliness and quality of health services provided by EMTs and enhance the capacity of national health systems in leading the activation and coordination of rapid response capacities aftermath of a disaster, outbreak and/or other emergencies. It adopts a rigorous and systematic approach to EMT registration, deployment, and response, It has set out benchmark requirements and standards for all EMTs and classifies all medical teams according to their capability into 4 main types (Appendix 1) [19]. The WHO-EMT initiative highlights that rehabilitation is one of the core components of regular health care and, as such, all EMTs (both national and international) should have specific and coordinated medical response plans for the provision of rehabilitation services to their patients [20]. Minimum technical standards and recommendations for rehabilitation for EMTs are published in collaboration with the ISPRM, and global rehabilitation experts (Appendix 2) [20]. It is a mandatory requirement that all EMTs, including specialized care teams comply and adhere to these principles and standards. The efficacious coordination, leadership and governance role of the EMT initiative was demonstrated in various natural disasters such as the 2013 typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, the 2015 tropical cyclone Pam in the Pacific region, 2015 Nepal earthquakes, and others [30,51]. A comprehensive registration system for all EMTs was initiated (since July 2015), which enables the establishment of a global EMT registry for future deployment (Appendix 3) [19]. To date, 37 acute medical/surgical teams (Type 1: 21, Type 2: 12, Type 3: 2 and 1 Specialized cell) from different parts of the world have progressed to full verification and many more teams have commenced the mentorship and quality assurance process. However, currently, any rehabilitation specialized cell is yet to be verified. Further various reports and guidelines, including specific clinical practice guidelines from different sources, are now published [52-54] and e-learning [55] professional development courses in disaster management are being developed (https://www.disasterready.org/).

Some of the key global initiatives related to disaster rehabilitation are summarised in Table 3 [20,26,51,56-67].

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Despite all aforementioned developments and significant improvements in emergency response and care, in many previous disasters rehabilitation services are less prioritised [12]. Further, many vulnerable cohorts, such as persons with disabilities and/or with pre-existing NCDs, etc., are often overlooked throughout the disaster management cycle. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) estimates that 71% of persons with disabilities do not have an individual preparedness plan for disasters and almost 85% have not participated in community disaster management and risk reduction processes in their communities [68]. Regrettably, significant disparities and gaps still exist among the countries, with those with high disaster risk having a low-coping capacity and scarce resources (infrastructure, skilled workforce, etc.) to address the challenges of the increasing frequency of disasters and their impact [6]. In many disaster-prone countries, rehabilitation-inclusive disaster management plans are absent and rehabilitation services are generally inadequate or underdeveloped [6,7,69]. For example, the density of skilled rehabilitation professionals in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is estimated to be 10 per 1 million population [70] and the unmet need is across many specialized rehabilitation services such as rehabilitation medicine, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, prosthetics and orthotics, and others [70]. There are also contrasts and imbalances within operational healthcare systems in many countries in terms of policies, funding structure/infrastructure, capacity, human and physical resources, technology, etc. Further, in large-scale disasters, even the world’s best healthcare systems can be overwhelmed due to damage and/or disruptions of local existing health service infrastructure and an influx of new victims. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is such an example that has tested the resilience of robust health systems of most developed countries, like the United States, Australia, France, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, etc [71]. Moreover, various barriers and gaps still exist in the comprehensive rehabilitation-inclusive disaster management process, which includes poor awareness, insufficient leadership and governance, inadequate coordination, financial constraints, limited political, etc [31, 72].

Global healthcare authorities acknowledge the important role of rehabilitation within the context of overarching disaster management systems and lack and/or limited rehabilitation services/workforce capacity can compromise outcomes. There is a need for effective action from national and international bodies for comprehensive rehabilitation-inclusive disaster responses to strengthen national capacity, and foster an environment of self-empowerment of rehabilitation medical personnel/teams for sustainable long-term care. This requires strong leadership from governing organizations and ‘shared’ responsibility from all actors in the field [31]. Various perspectives need to be considered for effective future disaster management, which include (but are not limited to):

• Strengthen robust collaboration and governance from healthcare organisations

• Strengthen political commitment and allocation of adequate resources at the highest level to rehabilitation inclusive disaster management process

• Emphasise on disaster risk reduction and climate change mitigation

• Accelerate capacity building and training for skilled interdisciplinary rehabilitation workforce

• Increase public awareness and education

• Persistent and timely communication with the public, healthcare workers, government agencies, and industry

• Training and educational programs for healthcare professionals regarding rehabilitation-inclusive disasters management

• Embrace a system-wide approach for rehabilitation-inclusive disaster planning, with active participation/inclusion of disaster survivors/family, persons with disabilities, other stakeholders and the community at large

• Strengthen access to rehabilitation services including assistive devices

• Develop effective strategies for reaching/supporting vulnerable population cohorts during disasters (e.g., persons with disabilities)

• Development of innovative interventions and various alternative methods of service delivery including, telerehabilitation, rehabilitation in the home, mobile clinics

• Promote task shifting and coordination between international EMTs, local healthcare authorities and humanitarian actors

• Strengthen community-based rehabilitation and provision of long-term needs/support of disaster survivors

• Formulate a formal registry of accredited rehabilitation professionals for deployment to disaster settings

• Recognition of social and cultural barriers within the disaster settings

• Improve communication (information gathering, sharing and disseminating)

• Development of standardized assessment and monitoring tools, and injury-specific rehabilitation guidelines in disaster settings

• Strengthen research and data collection

CONCLUSION

Rehabilitation is an essential part of the disaster management and recovery process. It involves restoring the physical, psychological, and social functioning of affected individuals and can help to mitigate the long-term impacts of disasters (disabilities, health complications, mental health), improve QoL and provide an effective pathway to recovery and successful reintegration of the victims into the community, and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to disaster rehabilitation, there is evidence suggesting various interventions/strategies that can be employed to ensure that the process is effective and efficient. It can be a complex and often lengthy process and requires all-inclusive planning and coordination approaches including strong governance and coordination, engaging with stakeholders (including vulnerable population cohorts such as persons with disabilities), developing a plan of action, and focusing on a long-term continuum of care.

There is strong consensus amongst global health authorities that medical rehabilitation should be initiated in the immediate emergency response phase and should be continued post-disaster over a longer term. Despite this, rehabilitation services are often neglected in previous disasters and many disaster-prone countries still have low coping capacity and limited rehabilitation resources. The current endorsement of the landmark resolution by the World Health Assembly: “Strengthening Rehabilitation in Health Systems,” the WHO aims to support member states in prioritizing rehabilitation within their health systems, promoting equitable access to rehabilitation services, and integrating rehabilitation and assistive technology in its EMTs including addressing the long-term rehabilitation needs of people affected by emergencies. Further, the WHO-EMT initiative and now set out a structure and standardization for future medical team deployments (including rehabilitation) to ensure that quality care is provided to those in need. There are still lots of challenges ahead and successful and effective rehabilitation-inclusive disaster management will depend on the proficient leadership of the governing bodies (international and national), and the willingness and commitment of countries to build systematic advance planning and preparedness, and building local rehabilitation capacities (skilled workforce, infrastructure, funding) to ensure that effective and timely services are available to vulnerable communities at risk in future calamities.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

None.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Disaster Rehabilitation Committee, of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) and Disaster Rehabilitation Special Interest Group, Rehabilitation Medicine Society of Australia and New Zealand (RMSANZ) for their support. The views expressed in this article are of the authors only and not of the above‑mentioned committee.

Notes

Conceptualization: Amatya B. Methodology: Amatya B. Formal analysis: Amatya B, Khan F. Project administration: Amatya B. Visualization: Amatya B, Khan F. Writing – original draft: Amatya B. Writing – review and editing: Amatya B, Khan F. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.