Median Nerve Injury Caused by Brachial Plexus Block for Carpal Tunnel Release Surgery

Article information

Abstract

Carpal tunnel release is required to treat patients with severe carpal tunnel syndrome. The regional anesthesia of the upper limb by brachial plexus block (BPB) may be a good alternative to general anesthesia for carpal tunnel release surgery, because it results in less complications. However, the regional anesthesia still has various side effects, such as hematoma, infection, and peripheral neuropathy. We hereby report a rare case of median nerve injury caused by BPB for carpal tunnel release.

INTRODUCTION

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common compressive neuropathy, and surgical treatment is required when its symptoms are severe. Carpal tunnel release, which is the fundamental treatment, results in 86% of the patients experiencing reduced pain [1]. Despite the prevalence of the positive results, there are occasional complications, such as incomplete release of the carpal tunnel, infection, and nerve injury [2].

Recently, the use of brachial plexus block (BPB) has become common for carpal tunnel release, as an alternative to general anesthesia, because it results in fewer complications. However, nerve injury has occurred in 0.2%-19% of the patients after its use [3].

The present case was referred to our clinic for a lack of improvement of the symptoms after the carpal tunnel release. Damage to the median nerve by BPB has rarely been reported, but in this case, we found that the nerve injury was caused by BPB and not by a surgical complication. Detailed collection of history and physical and electrodiagnostic examinations were helpful in the diagnosis. Authors have observed clinical and electrodiagnostic improvement in patients through conservative treatment and follow-up examination. Here we report a case and review the literature.

CASE REPORT

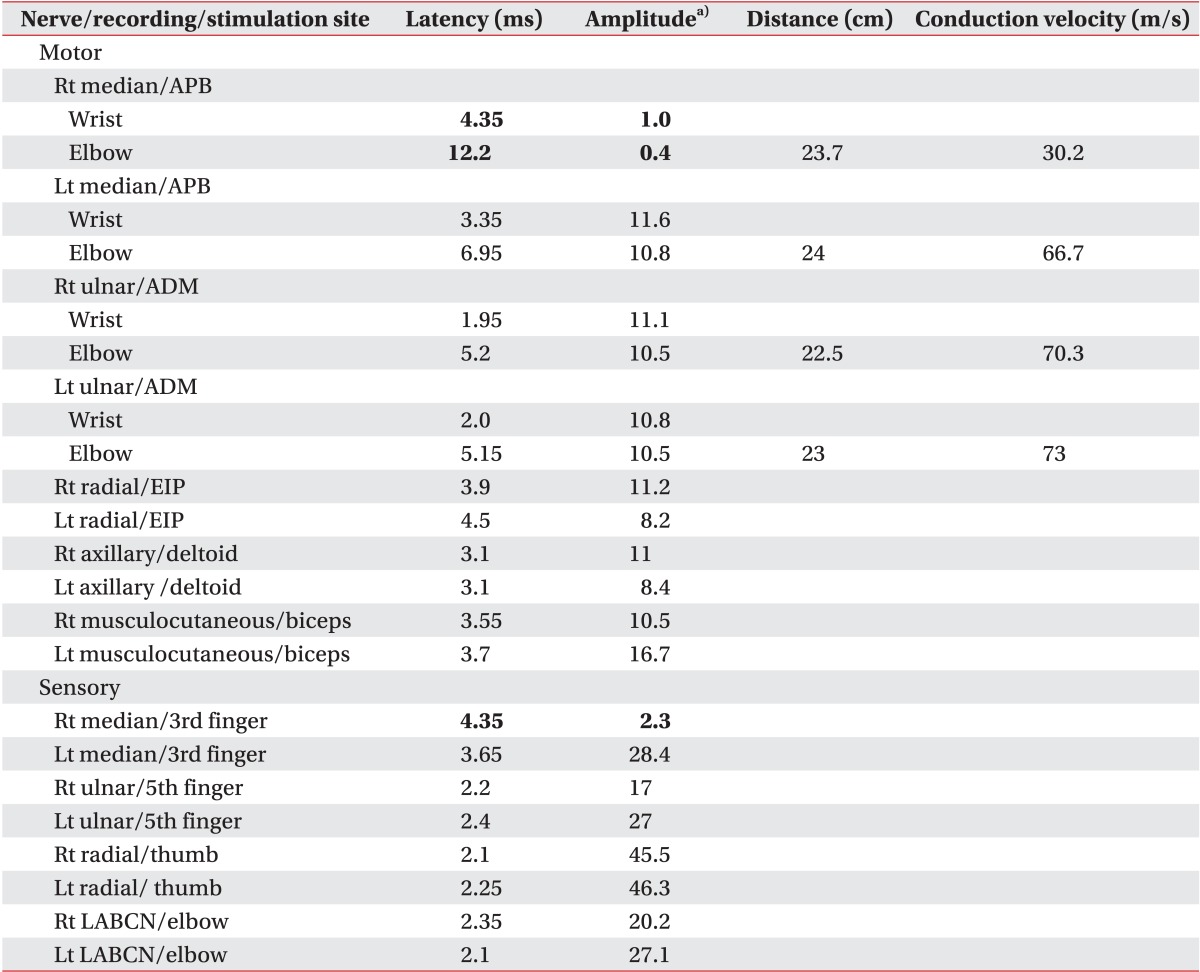

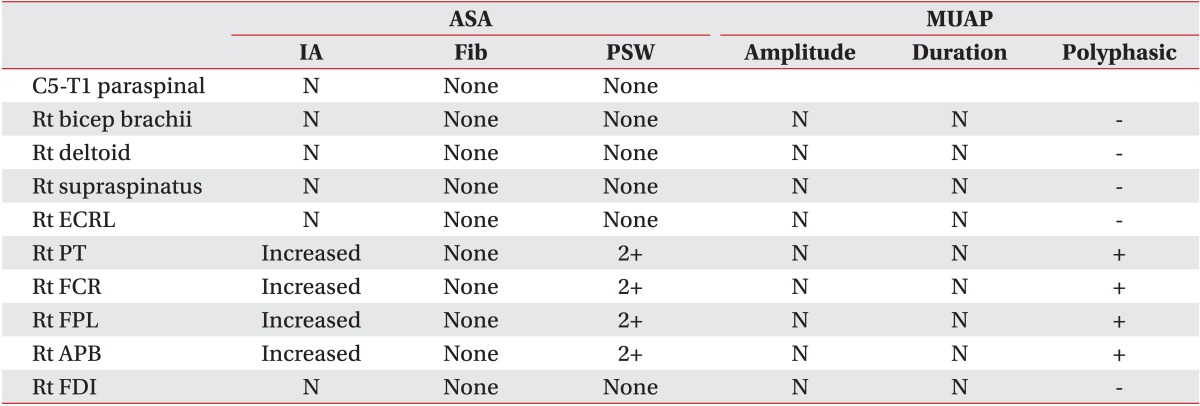

A 54-year-old female, who was diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome on the right side at another hospital, underwent carpal tunnel release about a month ago. After the operation, pain, hypesthesia, and hand numbness continued without improvement. Therefore, she was referred to our clinic for electrodiagnostic examination. On physical examination, no atrophy in the thenar eminence area was obviously visible, but muscular strengths of the wrist and finger flexor were reduced to the fair grade. Also, sense of the territory innervated by the median nerve was reduced. A nerve conduction study showed that the latencies of compound muscle action potentials and sensory nerve action potentials of the right median nerve were delayed, and the amplitudes of compound muscle action potential and sensory nerve action potentials of the right median nerve were reduced (Table 1). On needle electromyography, positive sharp waves and polyphasic muscle action potentials were observed in the right pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor pollicis longus, and abductor pollicis brevis muscles, and there were no abnormal findings in the other muscles (Table 2). On electrodiagnosis, median nerve injury was presumed at the level of the terminal branch of the brachial plexus. Before the electrodiagnostic study, we suspected a surgical complication, such as an incomplete incision of the carpal tunnel. However, this finding did not support the electrodiagnostic results, so we collected detailed history of the preparation for the anesthesia. At the time of the BPB, the patient experienced severely radiating pain down the right arm. Therefore, we concluded that the patient's symptoms were caused by median nerve injury that occurred during the BPB.

After conservative treatment was continued, the follow-up electrodiagnostic examinations showed increased amplitude of the compound muscle action potential and sensory nerve action potential (Table 3). Clinical improvements including pain reduction and increased muscle strength were identified.

DISCUSSION

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common entrapment neuropathy. If conservative treatment does not lead to improvement, carpal tunnel release is necessary. This procedure is relatively simple and quick, so regional anesthesia using BPB is more commonly recommended than general anesthesia.

Axillary BPB by transarterial approach is simple and has fewer complications. However, peripheral nervous system injuries can occur through the followings: 1) direct needle trauma, 2) intraneural anesthetic injection, and 3) axillary arterial laceration. In addition, infraclavicular brachial plexus injury was reported in 0.2%-21% of the cases [4,5]. Tsao and Wilbourn [5] reported that the median nerve was most commonly affected, followed by the combined median and ulnar neuropathies in 13 cases, with brachial plexus injury after axillary BPB. In their study, medial brachial fascial compartment (MBFC) syndrome was suggested as one of the causes of median nerve injury. In MBFC syndrome, laceration of the axillary artery causes slow leakage of the blood within this compartment, and both hematoma and pseudoaneurysm formation caused nerve injury. Unlike other nerves exiting the MBFC at the level of the upper arm, median and ulnar nerves travel within the compartment to the level of the elbow. This probably explains why the median and ulnar nerves are most often affected in MBFC syndrome. In our case, we also considered MBFC syndrome a potential cause of median nerve injury.

Two different degrees of nerve injuries were observed. First, most patients had mild paresthesia on the first day after the operation (19% for axillary block); however, it lasted no more than 4 weeks [6]. Second, some patients (12% of cases) had long-term paresthesia [7]. In terms of prognosis, recovery status until 1 week after surgery could be an important prognostic factor. If there is no improvement in sensory function for 3-4 weeks or no recovery of motor function after 6-8 weeks after damage, prognosis is generally considered as poor [8]. In our case, it can be presumed that the prognosis was poor, because of the persistent sensory and motor dysfunction for 4 weeks after the surgery. However, improvement was noted during the follow-up tests, so the result was different from those of earlier studies.

On the other hand, complications during carpal tunnel release vary among surgical methods where 0.5%-7% are obtained by the open method and 1.8% are obtained by the endoscopic method, and laceration of the median nerve is most commonly reported complication [9,10]. We initially suspected these complications for our patient, but it was different from a case of an unsuccessful surgery. Hence, the detailed history taking and electrodiagnostic examination results led to a diagnosis of median nerve injury induced by BPB.

In conclusion, when a patient's condition worsens or does not improve after surgical release of carpal tunnel syndrome, it is important to consider not only the potential complications of surgical treatment, but also the possibility of a nerve injury induced by the use of regional anesthesia.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.