Postpartum Sacral Stress Fracture Mimicking Lumbar Radiculopathy in a Patient With Pregnancy-Associated Osteoporosis

Article information

Abstract

Postpartum sacral fracture is relatively rare, and its diagnosis is often delayed. We herein report such a case of a 28-year-old patient who presented with an insidious-onset lower back pain, left buttock pain, and radicular symptoms mimicking lumbar radiculopathy. Laboratory tests showed a decreased 25-hydroxy vitamin D level, and the bone mineral densitometry of both femurs was below the expected range. Plain radiographs of the lumbar spine and pelvis showed no definite abnormality, but lumbosacral spinal magnetic resonance imaging identified a left sacral fracture. Symptoms were alleviated with rest and oral analgesic treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Sacral fracture is a rare condition among pregnant or postpartum patients. Because of its subtle clinical and radiologic features, diagnosis is often missed. Patients usually present with low-back, buttock, or pelvic pain-with or without radiating pain to the lower extremity [1,2]. When radicular symptoms do accompany the pain however, it may distract clinicians from the proper diagnosis of sacral fracture.

Sacral stress fractures are categorized into two groups: fatigue and insufficiency fractures. Fatigue fracture is caused by repetitive stress when a bony structure is intact, whereas insufficiency fracture is caused by a weakened cortical structure under normal stress [1].

A few cases of pregnancy-related or postpartum sacral stress fracture have been reported worldwide. Among these, only one case of a pregnancy-related sacral insufficiency fracture was evaluated with bone mineral densitometry [3]. In addition and to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reported cases of sacral fatigue or insufficiency fracture associated with pregnancy in the Korean population. We herein report a rare case of postpartum sacral insufficiency fracture with accompanying pregnancy-associated osteoporosis.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old patient reported pain in the lower back and left buttock with radiation into the left lateral calf, foot, and toes. She had a first spontaneous vaginal delivery of a 3.7-kg baby 2 months prior to this hospital visit, and had been suffering from a mild back pain from third trimester of pregnancy.

Prior to pregnancy, the patient had no history of back pain and was 162 cm tall and weighed 45 kg, for a body mass index of 17.15. The patient's total weight gain during pregnancy was approximately 17 kg. By the time of hospital visit, she had lost 12 kg, and weighed 50 kg. She breastfed for 3 weeks after delivery. Her back pain became aggravated 2 months after childbirth without any trauma or strenuous activities. On physical examination, muscle functions were normal in both lower extremities, and the results of straight-leg-raise test were negative, but she did have hypesthesia in the left L5 and S1 dermatome. Focal tenderness was noted in the left sacroiliac joint area, and Patrick test was positive on the left side. The patient's gait showed an antalgic pattern secondary to pain.

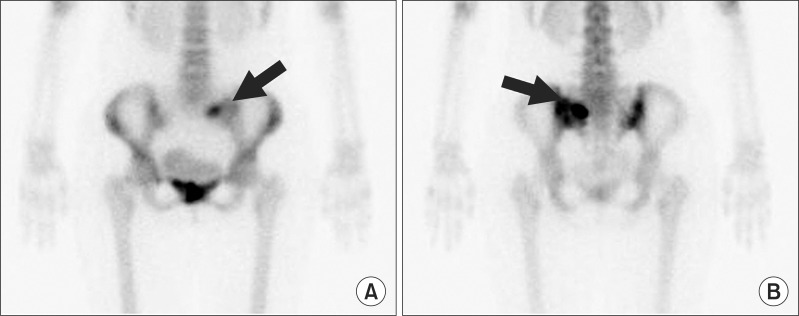

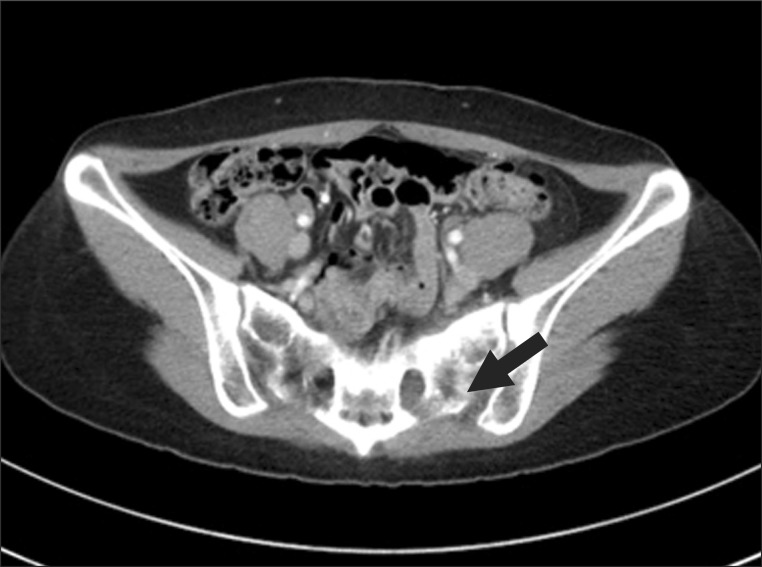

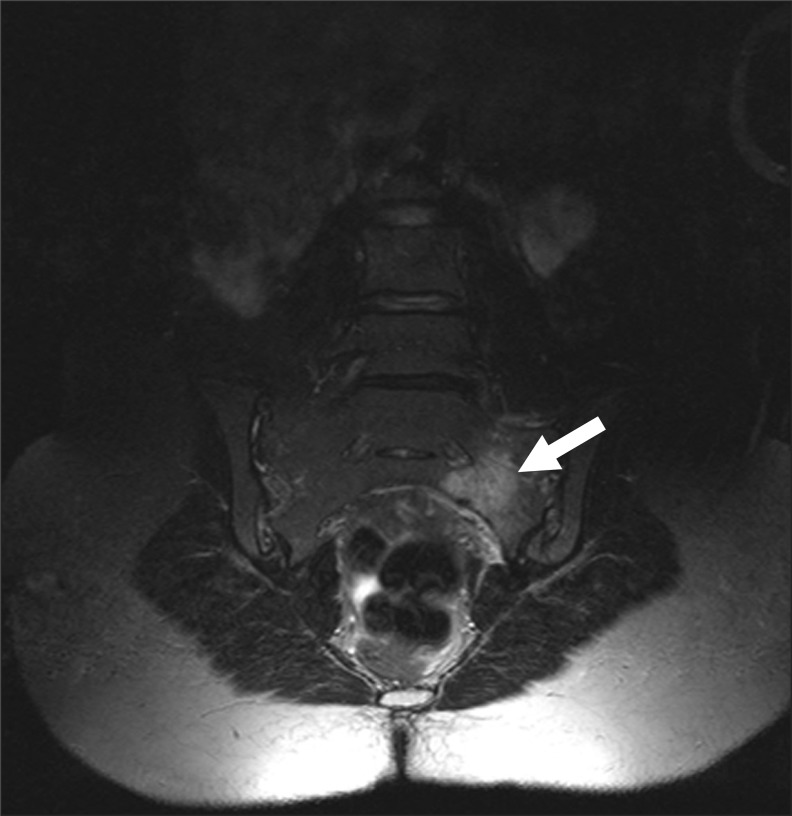

The initial diagnostic impression was that of a left L5 radiculopathy. Plain lumbar spine and pelvis radiographs showed no definite abnormality (Fig. 1). For further evaluation, lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and identified a non-displaced fracture of the left sacral ala surrounded by an osseous edema, suggesting a diagnosis of left sacral stress fracture (Fig. 2). A bone scan revealed an intense uptake in the left sacral ala area (Fig. 3), and pelvis computed tomography (CT) showed ill-defined sclerosis or mottled density in the left sacral ala (Fig. 4), confirming the diagnosis of left sacral stress fracture.

T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of lumbar spine showing increased signal uptake in the left sacrum.

In laboratory testing, renal, liver, and thyroid functions were within normal limits. Calcium and phosphate levels were normal, but 25-hydroxy vitamin D level was 13.1 ng/mL (normal range, 30.0-74.0 ng/mL). A follow-up dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry revealed z scores below the expected range for her age; z scores of the L1 to L4 spine and the right and left femur neck were -0.9, -2.0, and -2.0, with bone mass density of 1.058, 0.800, and 0.798 g/cm2, respectively.

The treatment consisted of rest from strenuous activities, light weight-bearing activities, adequate pain control, and the administration of vitamin D and calcium replacements. At the initial presentation, pain according to a visual analogue scale (VAS) was 6 on a scale of 0 to 10. At the 4.5-month follow-up visit, the VAS score had decreased to 1, and the antalgic gait pattern had disappeared almost completely.

DISCUSSION

Low-back, buttock, or pelvic pain is quite common in the prenatal and postpartum setting. The prevalence of low-back pain in the prenatal period is as high as 68.5%, and the prevalence of pregnancy-related pelvic pain is around 16% to 20% [4]. As in the case presented, most patients with sacral fracture complain of insidious-onset low-back or pelvic pain that may radiate to the groin, buttock, and thigh. The absence of acute trauma or strenuous activities at the onset of pain often distracts physicians from a diagnosis of fracture. The pain caused by sacral fracture is aggravated by exertion or weight-bearing and is relieved by rest. On physical examination, tenderness of the sacroiliac joint is often noticeable, and Gaenslen test, the squish test, and Patrick test are useful in evaluating sacroiliac joint pathology [5,6]. Limitations of physical activities may be present, and gait inspection usually reveals an antalgic pattern. Discogenic etiologies, vertebral compression fractures, central and/or foraminal spinal stenosis, facet arthropathy, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, hip pathology, and neoplasm are in the differential diagnoses for sacral fracture [7]. When nerve root irritation occurs by sacral fracture, radicular symptoms may accompany the pain, but the reported incidence of nerve root involvement is relatively rare and happens in approximately about 2% of all sacral fractures [8].

Radiologic investigations play a major role in confirming the diagnosis. In the acute phase, plain radiography of the pelvis and sacrum is usually nonspecific, and fracture lines may become visible only in the recovery phase as healing calcification develops. MRI is by far the most appropriate and accurate diagnostic tool, especially in pregnant and lactating women. Even in the acute phase of sacral fracture, bone marrow edema is easily visualized as a high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI views. Bone scintigraphy with technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate and CT are also useful diagnostic tools but are contraindicated in pregnant or lactating women.

Upon a definitive diagnosis, rest from strenuous activities, pain control with oral analgesics, and physical therapy constitute the mainstay of treatment. Early, light weight-bearing exercises should be encouraged to promote osteoblastic activities. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in fracture is currently under debate [6] because they are known to block the activities of prostaglandins-one of the main components in bone healing-and few retrospective studies have reported increased rates of non-union in long-bone fractures in association with the use of NSAIDs [9].

Our patient had a clear case of pregnancy-associated osteoporosis, which is closely associated with the incidence of sacral insufficiency fracture. The patient did not have any medical conditions that may cause secondary osteoporosis, such as thyroid disease, anorexia nervosa, or a medication history significant for corticosteroids or heparin. Considering the patient's report of outdoor activity and weight gain during pregnancy, poor nutritional status or lack of sun exposure would not have been a cause for the osteoporosis.

The incidence of pregnancy-related osteoporosis is approximately 0.4 cases per 100,000 women [2]. During pregnancy and lactation a woman's metabolism changes substantially to provide sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D to the growing fetus and newborn baby. Calcium absorption in the intestines is upregulated, and bone resorption is increased to meet the excess demand for calcium. Despite the changes in physiology, long-term risks of reduced bone density, osteoporosis, or fracture remain unchanged for most women through and after a pregnancy [10], but our patient did show lower bone mineral density for her age. For treatment, oral supplementation of calcium with vitamin D was prescribed.

Sacral stress fracture often goes undiagnosed and untreated. For postpartum patients with low-back, buttock, and radicular pain, stress fracture should be suspected in the differential diagnosis. Additionally, because low bone density is a well-known major risk factor for sacral insufficiency fracture, evaluation of bone mineral density should be performed in patients diagnosed with postpartum sacral stress fracture.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.