INTRODUCTION

Renal infarction is a rare disease that is often unrecognized due to its non-specific clinical presentations, which leads to the delay of diagnosis and treatment, causing serious renal dysfunction [1]. Renal infarction may be caused by various heart diseases, such as atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart diseases, mitral stenosis, and renal artery dissection, renal vein thrombosis, vasculitis and trauma [1]. One of these, the atrial fibrillation is a common heart disease that causes thromboembolisms, and is a main cause of ischemic cerebral infarctions, as well as renal infarction, mesenteric infarction and splenic infarction, which was rarely reported [2]. Abboud et al. [3] reports that among the 260 autopsies performed on patients expired by cerebral infarction, subdiaphragmatic visceral infarctions have been observed in 10.2%, with renal infarctions in 16.2% of these cases, being the most frequent. Abboud et al. [3] recommends that additional studies should be evaluated on subdiaphragmatic visceral infarctions in cerebral infarction patients, as it is frequently associated, but often non-symptomatic and easily diagnostically overlook. Abboud et al. [3] recommends that additional studies should be evaluated on subdiaphragmatic visceral infarctions in cerebral infarction patient due to its frequent association, but often non-symptomatic and easy diagnosis are overlooked.

The authors report a case study and literature reviews of multiorgan infarction, including splenic infarction, ischemic colitis and renal infarction, which occurred after the immediate use of anticoagulants after thrombolytic agents in a patient with ischemic cerebral infarction, and the proper use of thrombolytic agents and anticoagulants in patients with multiorgan infarction, due to atrial fibrillation.

CASE REPORT

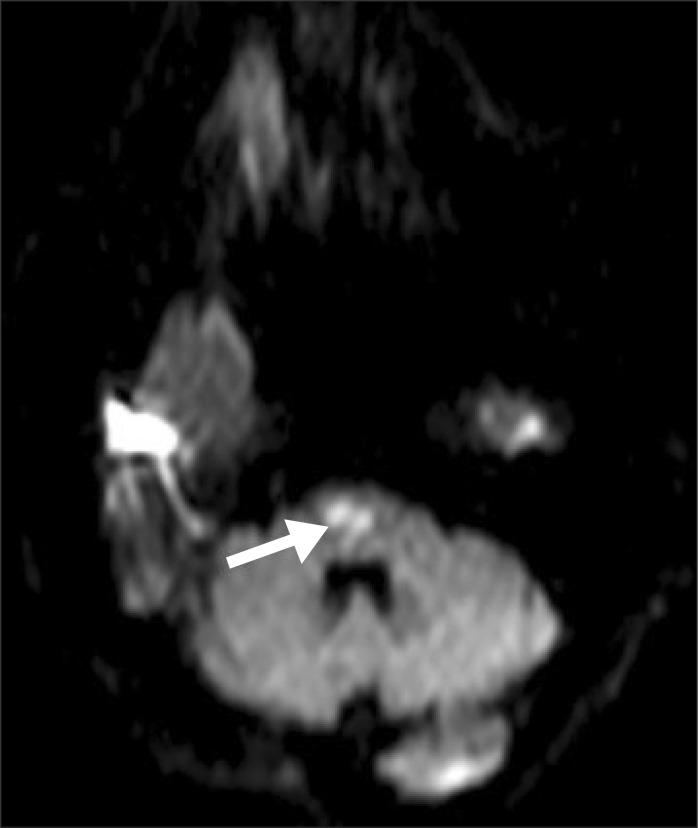

A 72-year-old male patient visited the emergency department with a sudden weakness of the upper and lower left extremity and dysarthria. The patient had a history of diabetes, congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation, and was currently taking 5 mg of warfarin, while maintaining an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0-2.5. The patient's blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, heart rate 66 bits/min, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min, and body temperature 36.8Ōäā. His mental state was clear with mild dysarthria by neurological exam. Manual Muscle Test grade (Medical Research Council of Great Britain) of his upper left extremity was 2, and lower left was 1. Patient's sensory examination showed normal findings, bilaterally. Brain magnetic resonance image showed that an acute cerebral infarction was recognized (Fig. 1), and low molecular weight heparin was used for 7 days, followed by oral administration of 3 mg warfarin after the 8th day.

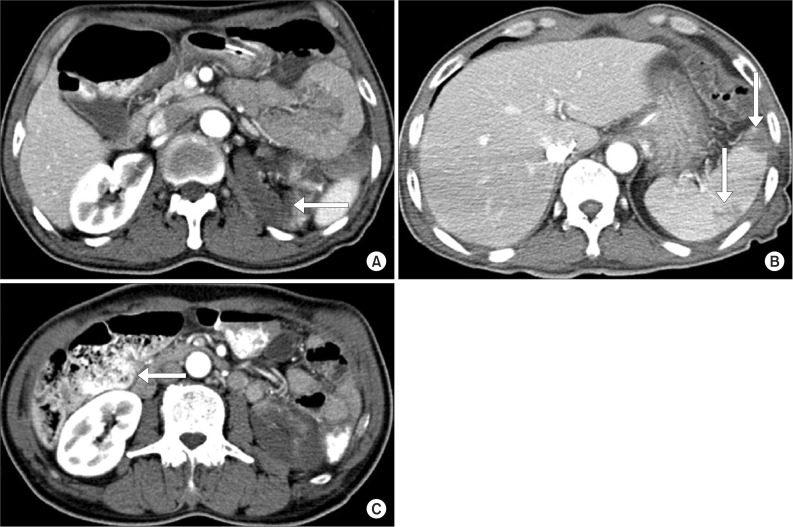

Thirteen days after the occurrence of cerebral infarction, the patient complained of mild abdominal pains, nausea, vomiting and presented with paralytic ileus in a simple abdominal X-ray. For physical examination performed on the 14th day, the patient complained the tenderness of the costovertebral angle which persisted during percussion. The laboratory examination showed increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 549 IU/L (normal range, 100-450 IU/L); white blood cell (WBC) 21.58├Ś103/┬ĄL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) 191/133 IU/L; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/Cr 41.4/1.43 mg/dL; C-reactive protein 65.6 mg/L; and procalcitonin 0.16 ng/mL, with INR 1.59. Urine analysis showed WBC 0-1/high power field (HPF), red blood cell 1-3/HPF and proteinuria. An abdominal computed tomogram (CT) showed a renal infarction with renal artery occlusion, multifocal splenic infarction and ischemic colitis on the rectum and sigmoid colon (Fig. 2). The patient could not be an indication for use of embolectomy and angiography after 24 hours since the abdominal pain and nausea. Low molecular weight heparin was administered intravenously for 10 days and followed by warfarin, maintaining a INR level of 2.0-3.0, with fluids and antibiotics for the accompanied ischemic colitis. A follow-up laboratory examination was performed after 25 days of occurrence, LDH levels normalized to 418, as well as normalization of AST/ALT 21/12 IU/L, BUN/Cr 16.0/1.02 mg/dL. A follow-up abdominal CT was performed after 43 days of occurrence. There was an improvement of the splenic infarction and ischemic colitis. However, signs of left renal infarction and atrophic change were observed (Fig. 3). During the 12-months follow-up after discharge, there was no symptom or sign of renal dysfunction, such as hypertension or renal failure.

DISCUSSION

Acute renal infarction is a rare disease, occupying 0.007% of patients admitted to the emergency department, which is also hard to diagnose early, taking an average 1.9 days to diagnosis after presenting such symptoms [4]. The reason of delayed diagnosis was its low occurrence rate, but mostly due to its frequent misdiagnosis as urinary stones, pyelonephritis, ischemic colitis, endocarditis and due to its various, non-specific clinical symptoms such as flank pains, abdominal pains, nauseas, lower back pains, and chest pains [4]. Therefore, an accurate understanding of the clinical manifestations, risk factors and diagnostic methods must be preceded for early diagnosis of renal infarction.

Examinations for the early diagnosis of renal infarction were urine analysis, hematologic exams, ultrasound, and CT. Hematuria or proteinuria is found in over 70% of urine analysis [5] and an increase of AST, ALT and LDH is known to be presented in hematologic exams. In renal infarction, the LDH is reported as the most sensitive laboratory finding, reaching 3 times of its normal value in less than 24 hours [1,6]. However, it showed low specificity, as the increase in LDH was also founded in other diseases, such as mesenteric infarction, hemolysis, infection in the abdominal cavity and myocardial infarction. There are currently many imaging methods for the diagnosis of renal infarction, but the most effective method for confirming the diagnosis is the angiography. However, there are some limitations due to its invasive nature and difficulties in its use on patients with restricted renal functions [1,5]. Ultrasound is a relatively non-expensive and easily-used method, though it is non-specific with low sensitivity, and has a low positive rate of 11%-20% in early diagnosis. However, ultrasound provides an advantage in excluding other renal diseases, such as urinary tract stones or obstructive urinary diseases [5]. Recently, CT was being used frequently due to its non-invasiveness and high accuracy. It also has advantages in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pains or surgical abdomens [1], and its most general sign was the low-density of triangular wedge-shaped renal infarction in patients [4].

This study is a case of a multiorgan infarction, including renal infarction, splenic infarction, and ischemic colitis, which occurred during the course of a transition between a 7-day long thrombolytic therapy and anticoagulation therapy for cerebral infarction, in a patient with underlining atrial fibrillation. In many cases, intravenous heparin is used before surgical or other procedures in patients with prolonged usage of anticoagulants. After these procedures, when switching from heparin to oral warfarin, bridge therapy was needed. Bridge therapy is a process of changing administration of one form of anticoagulant to other types of medications. Generally, during an intravenous heparin use, warfarin and heparin are both used for 2-3 days after the initiation of warfarin. This process induces proper anticoagulation effects after the transition to warfarin. Heparin administration is discontinued when INR reaches 2.0-3.0. Complications of bridge therapy, which include minor hemorrhage, major hemorrhage, death, thrombocytopenia, arterial and venous thromboembolisms, were known to occur by 16.2% [7]. In high risk groups, the combined use of intravenous heparin and warfarin, until the reach of a targeted INR, were safer, because when using warfarin only, proteins C and S were consumed first and it accelerates the production of thrombi. Maintaining the level of INR to 2.0-3.0 was important in the use of warfarin because the proper use of warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients is reported to lower the risk of thromboembolic strokes and systemic embolisms to 50% [2]. Researchers of atrial fibrillation acknowledge age, hypertension, history of cerebral hemorrhage, and heart failure as risk factors of cerebral infarction. The method of quantification for these risk factors was the CHADS2 score. A single point is given for heart failure, 1 point for hypertension, 1 point for ages over 75, 1 point for diabetes, and 2 points for recent cerebral infarctions or transient ischemic attacks [8]. In this case study, the CHADS2 score was 4, which falls under the criteria of high risk for a stroke event, 8.5% for each year if not administered warfarin [8]; therefore, in need of aggressive preventing measures.

Hazanov et al. [9] reported that during the administration of warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation, 66% of the renal infarction with atrial fibrillation patients showed the insufficient INR therapeutic levels of under 1.8. Furthermore, they recommended that exhaustive management of therapeutic levels were needed when administering the anticoagulation agents. Also in this case, the level of INR was 1.59 when multiorgan infarction occurred, which was lower than the therapeutic level.

There are conflicting arguments for the periods between manifestation of renal infarction symptoms and the moment of treatment initiation. One argument is that within 12 hours of renal infarction, the patient was able to undertake surgical treatments, such as thrombectomy, and after 24 hours, thrombolytic agents, such as heparin, is favorable if there are low associations between presented symptoms and treatment delay time. However, others argue that the time interval between blood vessel occlusion and its treatment is proportional with poor outcomes; therefore, fast diagnosis and treatments are preferred. In most cases, the conservative treatment was enough for renal function preservations; therefore, conservative therapy using heparin was applied [6].

The complications after renal infarction were known as renal function damages and hypertensions. Although it is known that hypertension occurs due to the activation of the renin-angiotensin system by the activation of plasma renin, its incidence rate varies among the reports and the relationship between the treatment of renal infarction and the regulation of hypertension is not yet clear [10]. In this case study, during the course of 12 months follow-up with the administration of anticoagulation agents, there were no symptoms or signs of complications, such as renal function damage or hypertension, and showed normal laboratory findings and no significant changes in CT findings.

Renal infarction is a rare disease, and it is difficult to diagnose and apply the proper early treatments due to its non-specific symptoms, which may lead to continuous renal function damages. Therefore, when a patient with a high risk of thromboembolisms presents signs of acute abdominal pain or flank pain, hematuria or proteinuria and an increase of LDH, AST and ALT levels in hematological exams, an early suspicion of renal infarction should be considered. For an early diagnosis of renal infarction, a CT scan was recommended. Also, high risk patients with high CHADS2 scores should need a proper bridge therapy with appropriate managed levels of INR when administering warfarin, they should also be considered for the possibilities of infarction occurring in multiple organs.