Spontaneous Cervical Epidural Hematoma Presenting as Brown-Sequard Syndrome Following Repetitive Korean Traditional Deep Bows

Article information

Abstract

Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma (SCEH) is an uncommon cause of acute nontraumatic myelopathy. SCEH presenting as Brown-Sequard syndrome is extremely rare. A 65-year-old man had motor weakness in the left extremities right after his mother's funeral. He received thrombolytic therapy under the impression of acute cerebral infarction at a local hospital. However, motor weakness of the left extremities became aggravated without mental change. After being transferred to our hospital, he showed motor weakness in the left extremities with diminished pain sensation in the right extremities. Diagnosis of SCEH was made by cervical magnetic resonance imaging. He underwent left C3 to C5 hemilaminectomy with hematoma removal. It is important for physicians to be aware that SCEH can be considered as one of the differential diagnoses of hemiplegia, since early diagnosis and management can influence the neurological outcome. We think that increased venous pressure owing to repetitive Korean traditional deep bows may be the cause of SCEH in this case.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is defined as epidural hemorrhage occurring without identified etiologies such as anticoagulation, hemophilia, neoplasm, arteriovenous malformation, trauma, or postoperative complications [1]. The cervicothoracic region is the most common region in which SSEH occurs [2]. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma (SCEH) generally presents acute neck or interscapular pain followed by radicular pain in the extremities. Progressive sensory loss or motor weakness of the limbs can be seen below the compressed spinal cord [1]. Brown-Sequard syndrome (BSS) as a presenting feature of SCEH is extremely rare [3,4]. We report our therapeutic experience on SCEH presenting as BSS and consider the pathomechanism of SCEH in this case.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old man (height, 168 cm; weight, 77 kg; body mass index, 27.3 kg/m2) developed a sudden onset of interscapular pain and motor weakness in the left extremities thereafter. He did not complain of any speech impediments, facial palsy or mental change. He had a history of hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus and he was on regular medical treatment for 5 years. He did not take any medications that could affect blood coagulations profiles, like antiplatelet agents. He also underwent nephrectomy and cholecystectomy a few decades ago. Before the onset of symptoms, he made more than two thousand Korean traditional deep bows for three days at his mother's funeral. Right after the last deep bow, he complained of sudden neck and interscapular pain. Brain computed tomography was checked at a local hospital and it showed no definite abnormalities. He received thrombolytic therapy under the impression of acute cerebral infarction. However, motor weakness of the left extremities became aggravated. After being transferred to our hospital, diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed, which revealed no evidence of acute cerebral infarction. Laboratory findings including complete blood count, coagulation profiles, and biochemistry profiles were unremarkable. A cervical spine MRI was performed for the evaluation of myelopathy and it displayed a longitudinal cervical epidural hematoma extending from the C2 to C6 vertebrae with a compression of the spinal cord (Fig. 1). He underwent left C3 to C5 hemilaminectomy with hematoma removal (Fig. 2). On hematoma evacuation, there was no bleeding or oozing. Two weeks later, he was referred to the rehabilitation unit. At that time, motor examination of the left upper extremity, using the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale, revealed 0/5 elbow flexors, 1/5 wrist extensors, 2/5 elbow extensors, 2/5 finger flexors, and 0/5 finger abductors. Motor examination of the left lower extremity showed 1/5 hip flexors, 4/5 knee extensors, 1/5 ankle dorsiflexors, 1/5 long toe extensors, and 2/5 ankle plantarflexors. On sensory examination, there was diminished sensation to pinpricks below C6 on the right. Clean intermittent catheterization was educated and performed as he could not urinate voluntarily. The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) was 25/100. He received rehabilitative management including neurophysiologic exercise therapy, functional occupational therapy, activities of daily living (ADL) training and functional electrical stimulation, consisting of 1 hour per session, 2 sessions a day, 5 days a week, for 4 months. At 5 months after the onset of symptoms, the left elbow flexors and finger abductors were 3/5. All other upper and lower extremities muscle groups were 4/5. Sensory examination showed decreased sensation to pinpricks below C7 on the right. He was able to ambulate with monocane and void voluntarily. SCIM improved to 80/100.

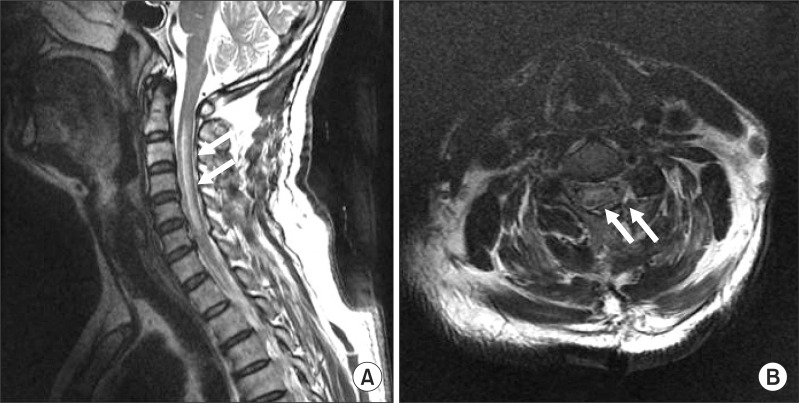

Magnetic resonance images of cervical spine. (A) T1-weighted sagittal image shows isosignal intensity epidural hematoma and compression of cervical spinal cord (arrows), and (B) T2-weighted sagittal image shows a longitudinal high-signal intensity epidural hematoma extending from C2 to C6 vertebrae (arrows). (C) T1-weighted axial image displays an ovoid isosignal intensity epidural hematoma with compression of the spinal cord (arrow), and (D) T2-weighted axial image displays an ovoid high-signal intensity epidural hematoma in the left posterolateral aspect with spinal cord compression (arrows).

Postoperative magnetic resonance images of cervical spine. (A) T2-weighted sagittal image shows swollen spinal cord and intramedullary high signal intensity from C3 to C6 and complete removal of previous cervical epidural hematoma (arrows). (B) T2-weighted axial image displays removal of previous epidural hematoma and evidence of the left C5 partial hemilaminectomy (arrows).

DISCUSSION

SSEH is a rare clinical entity [5]. SSEH usually presents acute pain in the affected region of the spinal cord with or without radicular symptoms [1]. Motor and sensory deficits are presented subsequently. SSEH most commonly involves the lower cervical region [1]. The lower cervical spine is the most active region in nonrotatory movements and the region where the brachial plexus arises. As the nerves in the lower cervical region have a greater excursion, they are vulnerable to injury [1]. The location of SCEH is usually posterior or posterolateral and hemorrhage usually extends over two to three segments [5]. Clinical presentations may differ according to the location or amount of hematoma. Bilateral neurological deficits are usual, but neurological deficits such as hemiplegia or monoplegia can be observed rarely [6].

The most common cause of hemiplegia is a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and other causes include spinal cord injury, especially BSS, trauma, bleeding, brain infections, and cancers. He initially exhibited motor weakness in the left extremities and interscapular pain. These clinical manifestations led to late diagnosis and an initial misdiagnosis of acute cerebral infarction without searching for other neurological signs.

In this case, acute compression of the spinal cord from left posterolateral SCEH caused BSS. When faced with a patient with hemiplegia but facial palsy, dysarthria, or mental change, other possible causes should be considered as well as CVA.

It is debated whether the origin of SSEH is venous or arterial [1,7,8]. The potential causes of SSEH include undiagnosed acquired or congenital coagulopathies, hypertension, increased venous pressure such as coughing, sneezing, sit-ups, and weight-lifting [7,9,10]. Sit-ups, weight lifting, or repetitive Korean traditional deep bows may involve the Valsalva maneuver, which may be accentuated by improper breathing [10]. A Valsalva maneuver increases intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressure. This is transferred to the spinal epidural venous system. The valveless nature of the epidural venous plexus has been thought to leave it vulnerable to abrupt changes in pressure and thus subject to rupture [7,8].

Upon further inquiry, he performed more than two thousand Korean traditional deep bows at the funeral rite for his mother before the onset of motor weakness. Deep bows have significance in Korean culture, because bows are performed frequently to show respect or grief in many Korean ceremonies. To perform Korean traditional deep bows, a man folds his hands together in front of his eyes in a standing position. Then he kneels and bows his head all the way down to the ground with his elbows out away from the body. After a while, he lifts his upper body to the kneeling position again. Repetitive performance of this deep bow may involve excessive cervical flexion and the Valsalva maneuver. To our knowledge, there has been no report on cervical epidural hematoma related to the repetitive cervical flexion movement with a Valsalva maneuver-like circumstance.

We could not exclude vascular malformations for certain, because angiography or biopsy was not performed. However, we excluded coagulopathy, considering the fact that he was not on any kind of medication related to bleeding complications and coagulation profiles were within normal limits. Although we cannot verify the direct cause of SCEH, we assume that the causes of SCEH in this case may be the preexisting weakened venous wall and increased venous pressure owing to the repetitive Korean traditional deep bows.

SSEH may be fatal if the diagnosis is late or prompt initiation of appropriate therapy is not started [1]. The most important predictors of neurological outcome are the interval between the onset of symptoms and surgical treatment and the preoperative neurological function [5,10]. Despite late diagnosis and surgical treatment, he actively participated in the rehabilitative management and showed progressive recovery. After one and a half years from the onset of symptoms, he could ambulate and perform ADLs independently.

Although SCEH presenting as BSS is quite rare, however, it should be considered as a differential diagnosis of hemiplegia. Further, repetitive spinal flexion movements, which have been frequently observed in Korean culture, may involve the Valsalva maneuver and have potential to develop a neurological event.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A084869).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.